The Checker Maven

The World's Most Widely Read Checkers and Draughts Publication

Bob Newell, Editor-in-Chief

Published every Saturday morning in Honolulu, Hawai`i

Noticing missing images? An explanation is here.

The Frue Vanner Machine

Picryl CC0

We're going to guess that very few if any of our loyal readers have ever heard of the Vanning process or the Frue Vanner machine, unless one of you happens to be a miner or mining historian. Vanning is a means of separating ore, and the Frue Vanner machine automates that process. It was invented in 1874 by a Canadian mine superintendent with the unsurprising name of W. B. Frue.

Did Mr. Frue play checkers? Perhaps. But his contemporary, one T. Vanner, certainly did, and is credited with correctly solving today's problem position, which is part of our ongoing Checker School series.

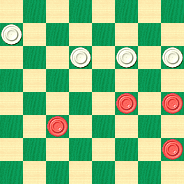

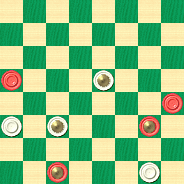

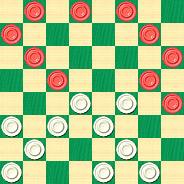

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W28,23,22,21:B14,13,11,5.

We won't say that this is an especially difficult problem, and mining for the solution will be like we suppose real-life mining to be at times: long and tedious and requiring care and caution. So dig deep for the winning method, and when you've extracted it, shovel your mouse to Read More to see the solution, sample games, and detailed notes.![]()

Sturges Steamroller

You wouldn't want to get in the way of the powerful looking machine shown above; it's something not to be tangled with. But today's entry from Willie Ryan's Tricks Traps & Shots of the Checkerboard is both powerful and tangled. It's a complex situation with quite a fine solution. Willie has a lot to say about it; take the time to play through the notes and variations to enhance your understanding and enjoyment of this one. With the help of modern computer analysis, we've added even more notes of our own.

| 11-15 | 16-20 | 8-11 |

| 23-18 | 24-19 | 29-25---C |

| 8-11 | 7-16 | 10-14---2 |

| 27-23 | 22-18 | 19-15---3 |

| 11-16---A | 4-8 | 3-8 |

| 18-11 | 25-22---B | 22-17---U. |

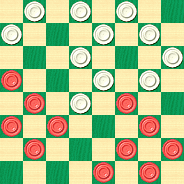

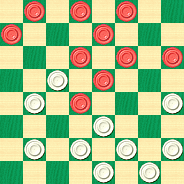

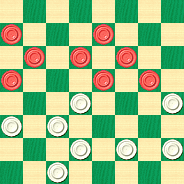

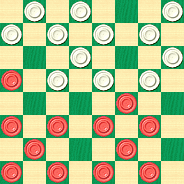

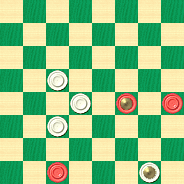

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W32,31,30,28,26,25,23,21,18,17,15:B20,16,14,12,11,9,8,6,5,2,1.

"At this point, white has fallen into a hoary snare, first shown by Joshua Sturges in 1800, which has been victimizing the innocents since its inception. The diagram shows the position after white's fateful faux pas."

A---With this move, black inaugurates the Slip Cross opening, one-time favorite of go-as-you-please players. Although white seems to have the upper hand on most variations of play, black's winning chances are by no means meager.

B---The only fertile move at this stage. If white takes 31-27, black can force a draw as follows: 31-27, 9-14, 18-9, 5-14, 25-22, 8-11, 28-24, 3-7, 22-18, 1-5, 18-9, 5-14, 26-22, 11-15, 22-17, 7-11*, 29-25, 6-9*, 17-13, 14-18*, 13-6, 2-9, 23-5, 16-23, 27-18, 20-27, 32-23, 15-29. J. Tonar.

C---In recent years, the prescribed move has been worn thin by wide and constant usage, and it is now being replaced by the lesser known 22-17---1, as follows:

| 22-17 | 5-14 | 18-9 | 2-7---F | 23-16 |

| 10-14---D | 29-25---E | 5-14 | 22-18 | 12-19 |

| 17-10 | 3-7 | 26-22 | 14-17 | 18-14 |

| 6-24 | 25-22 | 11-15 | 21-14 | 19-23---G, |

| 28-19 | 7-10 | 32-28 | 10-17 | ending in a |

| 9-14 | 22-18 | 15-24 | 19-15 | draw. |

| 18-9 | 1-5 | 28-19 | 16-19 | Frank Dunne. |

D---The great Frank Dunne, "King Kong" of yesteryear's draughts scribes, was the first to show play on this reduction, which at once throttles all threats by white. The move most frequently taken here is 9-14, although it is not so good as Dunne's 10-14 trouble eliminator. All the major points of the 9-14 line are outlined in the following play:

| 9-14 | 17-14 | 10-15 | 21-17 | 23-30 |

| 18-9 | 10-17 | 18-14 | 16-19 | 32-7; |

| 6-22---H | 21-5 | 15-18*---M | 10-7 | drawn. |

| 26-17 | 3-7 | 14-10 | 2-11 | Wm. F. |

| 5-9---K | 29-25 | 11-15* | 27-24 | Ryan. |

| 23-18---L | 7-10 | 31-27 | 20-27 | |

| 16-23 | 25-21 | 12-16* | 30-26 | |

E---White does not have any alternative play here worthy of mention. If he tries 26-22, then the countering play will be: 3-7, 29-25, 7-10, 22-18, 1-5, 18-9, 5-14, 25-22, and we are back to Note C, on the seventeenth move.

F---Another way to draw here is by: 20-24, 22-18, 24-28, 18-9, 28-32, 21-17, 32-28, 31-27, 2-7, 9-6, 7-11, 6-2, 11-15, 27-24, 16-20. Wm. F. Ryan.

G---Black has virtually forced the draw all the way from Note D (10-14). This is big league analysis.

H---Black is not really pinched here. The center jump also produces the draw; viz: 5-14, 29-25, 3-7*---I, 25-22, 11-15, 17-13, 15-24, 28-19, 14-17*, 21-14, 10-17, 22-18, 20-24, 18-15, 16-20, 19-16, 12-19, 23-16, 24-27, 32-23, 6-9, 13-6, 1-19. P. H. Ketchum vs. J. H. Scott.

I---A vital point in the defense. If 11-15 is tried, a draw by black is doubtful against the following play: 25-22, 15-24, 28-19, 20-24---J, 19-15, 10-19, 17-10, 6-15, 23-18, 24-27, 32-23.

J---A player by the name of J. S. Heyes attempted to show a draw here by 3-8, 17-13, 8-11, 22-18, 1-5, 18-9, 5-14, 26-22, 20-24, 22-18, 6-9, 13-6, 2-9, 31-26, 24-28, 26-22, 9-13, 18-9, 11-15, 9-6, 15-24; at this point Heyes recommended 23-18, which allows black to draw neatly by 24-27 etc.; but if instead of 23-18, you play 6-2, the win becomes obvious.

K---Several authors have claimed that this move is a losing one; but it may be played to a draw without exertion. At K, black can also draw by 3-7, 17-14 (if 29-25, 5-9, 23-18 are moved, Note D will apply), 10-17, 21-14, 1-6, 29-25, 6-9, 31-27, 9-18, 23-14, 16-23, 27-18, 11-16, 25-22, 20-24, 28-19, 16-23, 14-9, 5-14, 18-9, 7-11, 22-17, 11-15, 17-13, 15-19, 9-6, 2-9, 13-6, 12-16. A. E. Greenwood.

L---If 29-25 is played, then the draw comes about with: 9-14, 17-13, 3-7, 13-9, 11-15, 25-22, 15-24, 28-19, 7-11, 22-18, 20-24, 9-5, 16-20, 18-9, 24-27, 31-24, 20-27, 23-18, 27-31, 21-17, 11-16, 18-15, 16-23, 15-6, 1-10, 5-1, 10-15. Wm. F. Ryan.

M---The only move to draw. 11-16 loses and sets up a fine problem study by Champion John T. Bradford, American member of the 1927 International Checker Team. We illustrate the position (after 11-16) with a diagram on the next page---**."

U---The loser."

1---The computer, by a very slim margin, seems to still prefer 29-25, but Willie is talking about practical over-the-board play and not deep computer analysis---Ed.

2---The computer shows that Black has gone seriously astray here; 3-8 would have been correct---Ed.

3---31-27 was best to retain White's lead. This allows Black to get back in the game, but it took some extensive computer analysis to come up with this conclusion---Ed.

**---This will be the subject of next month's installment---Ed.

Willie made a couple of errors here, but it's hard to fault him. As the notes show, this particular run-up illustrates the difference between practical play over the board and detailed and often arcane computer analysis. In the end, checkers is intended for humans! In any case, can you find the win? Can you correct the play at Note U and find the drawing line?

Don't let our double challenge steamroller you. Solve the problem and then roll your mouse over to Read More to see the solutions.![]()

Acclat

Now here's one that puzzled us a great deal. "Acclat" is the pen name of the problemist credited with today's Checker School entry, but we turned up little on the word itself. We found two companies, Acclat Famous Urban Apparel, seemingly not famous at all, and Acclat Business Solutions, at least equally obscure, but little else of any interest.

Acclat sounds French, but the French word is really éclat as in the common expression éclat de rire, a peal of laughter. But acclat? It will remain a mystery.

Hopefully our problem position, shown below, will prove far less mysterious.

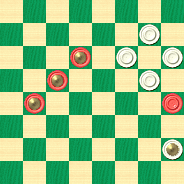

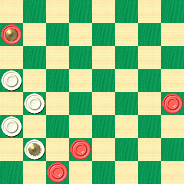

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W32,K22,21,K15:BK30,K24,20,13.

We'd say that this one, while certainly not easy, is at least quite a little bit easier than most Checker School selections, and you're likely to have your own éclat de rire when you see the solution. Still, checkers is no laughing matter, so keep a straight face and solve the problem, and then click on Read More for the solution, a sample game, and detailed notes.![]()

Mauro's Seesaw Stroke

Who wasn't fond of the see-saw or teeter-totter as a child? Of course, there were always those kids on the other end who would slam you down as hard as possible or try to throw you off, but by and large we all had a great deal of fun on these simple but entertaining playground toys.

Today's selection from Willie Ryan's Tricks Traps & Shots of the Checkerboard may definitely throw you off and even possibly slam you, but it's one of the best in his book, and that's saying a lot. Let's tune in to Willie as he tells us what it's all about.

| 11-15 | 21-14 | 24-20---2 | |

| 21-17 | 6-10 | 4-8---3 | |

| 9-13 | 22-17 | 29-25 | |

| 25-21 | 13-22 | 11-15 | |

| 8-11 | 26-17 | 30-26 | |

| 17-14---1 | 15-18 | 8-11---A | |

| 10-17 |

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W32,31,28,27,26,25,23,20,17,14:B18,15,12,11,10,7,5,3,2,1.

A---"Though this move loses, I can find no published play showing how to beat it. In view of the very delicate nature of the win after 8-11 is played, it appears that the possibilities of the gambit have been overlooked. Oliver J. Mauro. At this point, the correct play for black is: 15-19, 23-16, 12-19, 27-23, 18-27, 32-16, 8-12, 16-11*, 7-16, 20-11, 2-7, 11-2, 1-6, 2-9, 12-16, 14-7, 5-30, 28-24*, 30-23, 24-20, 3-10, 20-11. Sweeney vs. Truax.

Another choice at A is 2-6, but white wins against this move with: 26-22, 6-9, 23-19, 15-24, 22-6, 1-10, 28-19, 9-18, 19-16, 12-19, 27-23, 19-26, 31-6. James Wyllie."

1---While it certainly can't be said that this move loses, it's surely inferior. 30-25 or 24-19 is best here---Ed..

2---White makes his situation worse and ends up with a definitely inferior position. 23-19 is better---Ed..

3---With this move Black dissipates all his advantage. 1-6 would keep a clear edge and 2-6 is almost as good---Ed.

There isn't any doubt that this one is tough, perhaps unfairly so, and we think it may be within the capabilities of only the top players. Still, it's really, really good and definitely worth your time, even if you end up looking at the solution before very long. Make use of your computer to explore various alternative lines and enjoy this fascinating position. You'll understand Willie's title of "Seesaw" when you see the various lines of play in the solution.

So don't be swayed by the apparent difficulty; take a few swings and bear with the inevitable ups and downs. Then click on Read More to see the solution and detailed notes.![]()

Let's Play Checkers

It's been a long time coming, but thanks to the kind approval of the Grover estate, we're at long last able to offer a new electronic edition of the Ken Grover and Tom Wiswell classic, Let's Play Checkers.

This book, originally published back in 1940, went through a number of editions, most of them during wartime. The copies have not fared well. Wartime paper restrictions limited the quality and especially the durability of the books, and although used copies can still be had, they vary greatly as to their condition.

Our new edition features modern typography and clear, crisp board diagrams, while still retaining all of the wonderful content and "feel" of the original.

Let's Play Checkers was not your typical checker book. Though it did have the usual "Game Section" and "Problem Section" structure common to nearly all books of the time, the emphasis was decidedly different. Let's Play Checkers is an opening repertoire book for the go-as-you-please (GAYP) player.

Repertoire books, which feature detailed study of just a few suggested game openings, are common in chess but most rare in checkers. Let's Play Checkers' repertoire approach will appeal to the intermediate GAYP player, while its sparkling collection of 100 problems will attract players of every skill level.

Here's an example, composed by co-author Ken Grover.

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W30,28,27,26,22,21,20,18:B16,15,13,11,10,9,7,5.

This is a book you'll definitely want, even if you already have a print copy, and it's yours for the taking, completely free of charge. You can download it here. So what are you waiting for?![]()

The Fugitive King

Perhaps the most famous royal fugitive, King David, is to be found in the Scriptures. He spent 15 years in exile, fleeing from King Saul. Strictly speaking, David wasn't yet a king during his fugitive years, but he is nevertheless often referred to as "The Fugitive King."

Today's entry in our Checker School series deals with a checker-related "Fugitive King" theme. This problem is reminiscent of the "Fortress" situations that we've covered in several earlier columns, although here if Black plays correctly the White king will find no refuge.

WHITE

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W25,22,21,17,K5:BK23,K19,K16,13.

The problem requires very precise play and the solution is not short. We certainly have to rate this one as quite difficult. But don't go on the lam; try to solve it! When you're finished, run your mouse over to Read More to see the solution, a sample game, and detailed notes.![]()

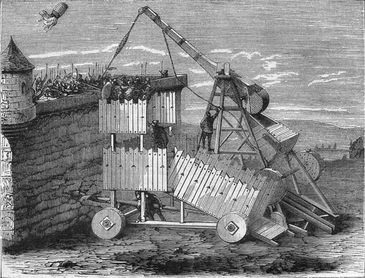

Lieber's Catapult

Picryl CC0

You're likely to see catapults similar to the one shown above in many an epic movie set in the Medieval period. They were fearsome siege devices; they would sling heavy rocks or Greek fire over a substantial distance in an effort to breach the defenses of the targeted castle.

In today's entry from Tricks, Traps & Shots of the Checkerboard, Willie Ryan's classic, we present an aptly-named catapult in our game of checkers. Here's Willie's run-up and very brief description.

9-14, 22-18, 5-9, 24-19, 11-16, 26-22, 7-11---A, 22-17, 16-20---2, 30-26---B

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W32,31,29,28,27,26,25,23,21,19,18,17:B20,14,12,11,10,9,8,6,4,3,2,1.

A---"A somewhat inferior line of play---1, but the trap at B is well concealed.

B---Caught!"

1---We're not really sure why Willie calls this move inferior, as it seems to be the best move, with the computer evaluating 10-15 as slightly worse---Ed.

2---Definitely inferior to 11-15. Perhaps Willie misplaced Note A and meant to put it here---Ed.

Can you take the leap and solve this one? While you're finding the winning Black move, spring back and correct White's losing play at 30-26. This isn't a shot in the dark; it's scientific checkers at its best. When you're finished, fling your mouse to Read More to see the solutions and detailed notes.![]()

A Thinker's Game

Those of us who play checkers in any sort of serious manner know very well that checkers is indeed a "thinker's" game, despite our oft-repeated laments that the general public doesn't usually share that opinion. Today's entry in our ongoing Checker School series demonstrates the fine line that can separate victory from just another drawn game; it takes a real thinker to see the difference between moves that look very similar but are far from it.

The situation is diagrammed below.

WHITE

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W20,16,12,K8:BK28,13,7,3.

You'll see in the solution notes and sample game the interesting manner in which this position came about, but for now, can you think your way to a Black victory, or will a thoughtless move give up your winning chances? Think it over, and then click on Read More to see the solution, thoughtful notes, and a sample game.![]()

The Jaywalker Gambit

If you visit Honolulu, you'd best not jaywalk; the fine is a whopping one hundred and thirty dollars, and the police don't hesitate to hand out the tickets. Jaywalking is a gambit you won't want to risk; it could really cost you.

There's a Jaywalker Gambit in checkers, too, and it won't cost you a cent to hear how Willie Ryan describes it in his classic book, Tricks Traps & Shots of the Checkerboard.

"The late great A. J. Heffner, of Boston, former Champion of America and heralded as one of the greatest analysts of all time, was responsible for christening the following trap 'the Jaywalker,' pointing out that many experts had wandered into it, unaware of their predicament until it was too late to bail out. The Jaywalker, a formational 'natural,' was originally rated drawable on the basis of Tillum and Aitchison's play, as quoted in the trunk game. But the eminent British authority, J. A. Kear, of Bristol, England, published an analysis indicating that, by introducing the 16-19 move at Note E, the gambit ended in defeat. Kear's play remained unchallenged for many years, but the data assembled here indicate that Kear's 16-19 move is nothing more than a transposition that ultimately runs back into the Tillum and Aitchison draw. Play:

| 11-16 | 30-26 | 7-10 |

| 24-19 | 11-16 | 26-22---2 |

| 8-11 | 22-17---A | 10-14, |

| 22-18 | 4-8 | forming the |

| 10-14 | 17-10 | diagram. |

| 26-22 | 6-24 | |

| 16-20 | 28-19 | |

WHITE

White to Play and Draw

W:W32,31,29,27,25,23,22,21,19,18:B20,16,14,12,9,8,5,3,2,1.

A---A very weak move---1, forming the famous Jaywalker position. The correct play here for a draw is: 28-24, 4-8, 22-17, 7-10, 26-22, 3-7---B, 19-15, 10-26, 17-3, 26-30, 18-15, 6-10, 15-6, 1-10, 31-26, 30-23, 27-18, 20-27, 32-23, 9-13, 21-17, 5-9, 25-21, 2-7, 29-25, 7-11, 3-7, 10-14, 17-10, 16-20, 7-16, 12-26. Wm. F. Ryan.

B---White has a pretty trap here, for if the play goes 9-13, 18-9, 5-14, white wins by storm with: 19-15!, 10-26, 17-10, 6-15, 22-17, 13-22, 25-4, 26-30, 4-8. D. G. McKelvie."

1---The computer sees 22-17 as only very slightly worse than 28-24, so we're not sure why Willie thinks it's so weak. Perhaps the position is simply more difficult to play correctly---Ed.

2---Here's the real problem. The text move is substantially weaker than 25-22, though still not losing. Perhaps Willie should have flagged this move instead---Ed.

Don't be a jaywalker; walk the straight and narrow and solve the position. But we won't fine you if you don't get it; you can always safely click on Read More to see the solution and detailed notes.![]()

Are You Dunne, Yoeman?

There are various definitions of the word yeoman. The most well-known dates to the Middle Ages and refers to an independent landowner, usually of a small parcel, who farmed the land for a living. But yeoman is a naval rank in both the British and American armed forces, and of course yeoman is also a rank in the celebrated Star Trek television series. And then there are the Yeoman of the Guard.

Our picture above, however, is closer to home; it shows surfer Nathan Yeoman skilfully riding one of the heavies at the Banzai Pipeline on the famed North Shore of O`ahu.

There is a checker yeoman, too, or more correctly, Yoemans. He's partnered in with Frank Dunne in the pair of positions below, which form this month's Checker School offering.

BLACK

WHITE

White to Play and Draw

W:WK32,30,K15:BK27,23,21,K6.

J. R. YOEMANS

WHITE

BLACK

Black to Play and Draw

B:W19,15,11,K1:BK14,13,3.

You may not be a Yeoman of the Guard, and it's unlikely (though certainly possible) that you've surfed the Pipeline, but we know you play checkers, and you can be a "Yeoman of Checkers" if you solve these problems. Give it your best and when you've caught the wave, click on Read More for the solutions, a sample game, and detailed notes.![]()

The Checker Maven is produced at editorial offices in Honolulu, Hawai`i, as a completely non-commercial public service from which no income is obtained or sought. Original material is Copyright © 2004-2026 Avi Gobbler Publishing. Other material is public domain, AI generated, as attributed, or licensed under CC1, CC2, CC3 or CC4. Information presented on this site is offered as-is, at no cost, and bears no express or implied warranty as to accuracy or usability. You agree that you use such information entirely at your own risk. No liabilities of any kind under any legal theory whatsoever are accepted. The Checker Maven is dedicated to the memory of Mr. Bob Newell, Sr.