The Checker Maven

The World's Most Widely Read Checkers and Draughts Publication

Bob Newell, Editor-in-Chief

Published every Saturday morning in Honolulu, Hawai`i

Noticing missing images? An explanation is here.

Do As I Say

"Do as I say, not as I do" is an old expression that finds application all too often. We can think of far too many examples to list here, so we'll just invite you to use your imagination.

In a scientific game such as checkers, though, it would seem that such a catchphrase has little application. After all, checker moves speak for themselves; they're either good or they're not. But bear with us; following the solution to today's problem you'll find a hilarious example of one man's version of "Do as I say" over the checkerboard.

The position, part of our Checker School series, is subtle and pleasing, and as usual, highly practical.

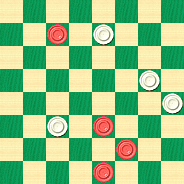

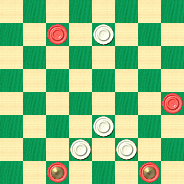

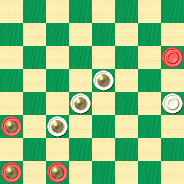

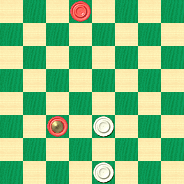

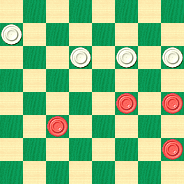

WHITE

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W26,17,13,11:B27,10,6,2.

It's harder than it looks. Can you solve it? When you've found your solution, click on Read More to check your answer and play through a sample game with explanatory notes.![]()

Diagonal Diagnosis

Editor's Note: This column has been substantially corrected thanks to correspondence from checker expert Al Lyman.

The photo above shows a nasty diagonal crack in the foundation of someone's house. That's going to be an expensive problem but it's best to diagnose and fix it before it gets worse.

As we mentioned in our previous installment from Willie Ryan's Tricks Traps & Shots of the Checkerboard, we're getting toward the end of the book and Willie's examples have turned even more complex than ever. In today's installment, Willie, who lacked powerful 21st century computing capabilities, had a few of his own diagonal cracks in the foundation of his analysis. Still, it's hard to fault such a brilliant man; he was doing everything in his head with no silicon monsters to help him out, and he got it right far more often than not.

Today, we're asking you to repair the cracks, and we understand that that's a tall order indeed. But we think you'll enjoy and benefit from our revised analysis, all of which is attributed to Ed Gilbert's KingsRow computer engine and 10-piece endgame database. Think what Willie would have done with such fabulous tools. No more patching by hand!

| 9-13 | 18-9 | 13-22 | 1-5 | 12-16 |

| 21-17 | 5-14 | 20-16* | 11-15 | 17-13 |

| 11-15 | 24-20---I,4 | 11-18---O | 5-9 | 18-23 |

| 25-21 | 3-8---J | 19-15 | 8-11 | 24-20---9 |

| 8-11 | 28-24 | 10-28 | 27-24 | White |

| 23-18---1 | 1-6*---K | 30-26 | 4-8 | should |

| 6-9---2 | 23-19*---5 | 12-19 | 21-17 | win. |

| 26-23---A | 15-18---N,6 | 26-1*---P | 8-12 | Wm. F. |

| 9-14---B,3 | 22-15 | 7-11---7 | 29-25---8 | Ryan. |

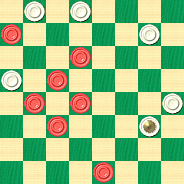

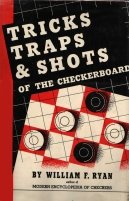

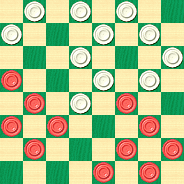

BLACK

Black to Play and Draw

B:W32,31,25,20,13,K9:B28,23,19,16,15,11,2.

A---"The orthodox continuation here is: 27-23, 9-14, 18-9, 5-14, 30-25, 1-6, 24-19, etc. While the 26-23 line is not so safe, it is sound enough, and is considerably more productive of wins than the conservative 27-23 development.

B---3-8 is stronger at this point and has been published erroneously as a play to win for black. The following outline charts the course to safety for white:

| 3-8 | 32-27* | 6-9 | 23-18 | 19-23 |

| 23-19* | 1-6 | 31-27---G | 27-24 | 2-7 |

| 11-16---C | 30-26* | 7-10 | 18-15 | 23-18 |

| 18-11 | 10-15---E | 28-24 | 24-19 | 1-6 |

| 16-23 | 20-16* | 19-28 | 15-10---H | 18-25 |

| 27-18 | 2-1---F | 27-24 | 4-8 | 7-10 |

| 8-15 | 27-23* | 12-19 | 6-1 | 13-22 |

| 18-11 | 15-18 | 24-6 | 8-11 | 6-13* |

| 7-16---D | 23-14* | 28-32 | 10-6 | Drawn. |

| 24-20* | 9-25 | 26-23 | 11-15 | Wm. F. |

| 16-19 | 29-22 | 32-27 | 6-2 | Ryan. |

C---If the moves are: 9-14, 18-9, 5-14, then the draw is reached with: 30-25*, 11-16, 24-20, 15-24, 28-19,16-23, 27-9,1-5,17-14, 10-26, 31-22, 5-14, 22-17, 13-22, 25-9. Wm. F. Ryan.

D---Abandoned here by P. H. Ketchum without further play. He judged the situation to be strong for black, if not a win. The route to a draw from this point involves instructive analysis.

E---4-8 is a low-pressure alternative and barely gains a draw, viz: 4-8, 27-24*, 2-7, 24-15, 10-19, 22-18*, 13-22, 26-17, 9-13*, 17-14, 6-9*, 29-25, 8-11*, 31-27, 19-23, 27-24, 13-17, 24-19, 17-22, 21-17, 22-29, 17-13, 29-25, 13-6, 23-26, 6-1, 25-21, 1-6, 21-17, 6-10, 5-9, 10-3, 17-10, 3-8, 10-14. Wm. F. Ryan.

F---Or 6-10, 27-24, 9-14, 16-11, 12-16, 31-27*, 5-9, 29-25*, 16-20, 11-7, 2-11, 27-23, 20-27, 23-7, 27-31, 26-23, 31-27, 23-19, 15-24, 28-19, which also produces a draw. Wm. F. Ryan.

G---A more difficult draw may be effected with careful play by 22-18,13-22, 26-17, 9-13, 17-14, 19-23, 18-15, 12-19,15-10, 5-9, 10-3, 9-18, 3-7, 18-22, 7-10, 22-25, 10-15, 4-8, 15-24, 8-12, 24-20, 25-29, 28-24. Wm. F. Ryan.

H---The position is now clearly a draw, but we continue the play to illustrate a fancy as well as feasible finish.

I---White has the best looking board, with virtually all of the winning chances in his favor.

J---The build-up by 4-8, 28-24, 1-6, 23-18 is a creaky combination for black, but 15-19, 23-16, 12-19 will do well; at this point, continue with: 27-24, 10-15* (not 11-15, 22-18*, 15-22, 24-6, 1-10, 32-27 *, etc., as white will win; I have victimized many a player with this scheme) 17-10, 7-14, 30-26, 2-7, 32-27, 4-8, 27-23* (not 22-17, 13-22, 26-10, 7-14, 31-26, 14-18, 26-22, 18-25, 29-22, 1-5, 21-17, 5-9, 17-13, 9-14, 13-9, 14-18, 22-17, 19-23, as black will win. Paul Thompson); 8-12, 23-16, 12-19, 22-17, 13-22, 26-10, 7-14, 31-26*, 14-18, 26-22, 18-25, 29-22, 19-23, 24-19, 15-24, 28-19, 23-26, 22-18, 26-30, 19-16, 30-25, 16-7, 3-10, 21-17, ending in a draw. Wm. F. Ryan.

K---Black's only move to draw. The three alternatives, 1-5, 11-16, and 12-16, all lose in short order as follows:

| 1-5---L | 15-24 | 10-19 | 13-17 | 12-16 |

| 30-25* | 27-11* | 17-10 | 21-5 | 31-26 |

| 5-9---M | 8-15 | 19-23 | 30-21 | 16-19 |

| 32-28* | 23-19* | 10-6* | 18-14 | 26-22 |

| 11-16 | 15-24 | 23-26 | 21-17 | 19-23 |

| 20-11 | 28-19 | 6-1 | 14-9 | 29-25. |

| 7-16 | 4-8 | 26-30 | 17-14 | White |

| 24-19* | 19-15 | 22-18 | 1-6 | wins. |

L---If the play goes: 11-16, 20-11, 7-16, white triumphs with 23-18, 14-23, 27-11, 8-15, 30-26, 16-20, 17-14, 10-17, 21-14, 20-27, 31-24. Again at L, if 12-16 is the play, white romps home first with: 23-19, 16-23, 27-9, 1-5, 9-6, 2-9, 30-26, 9-14, 26-23, 8-12, 35-19, 14-18, 29-25, 5-9, 32-27, 9-14, 31-26, 4-8, 26-23. Wm. F. Ryan.

M---Against 11-16, 20-11, 7-16, white executes a very unique clean-out and wins with: 23-19*, 16-23, 27-9, 5-14, 22-18*, 14-23, 31-27, 13-22, 25-11, 8-15, 27-11.

N---Loses, and white snaps the trap shut with a startling stroke, which has claimed many a champion. I was caught by this one several times before I came to recognize it; and I saw Newell W. Banks entrapped by it as well. The following play at N assures a draw and makes white run hard for home: 6-9*, 30-25*, 11-16, 20-11, 7-23, 27-11, 8-15, 24-19*!, 15-24, 32-28, 24-27, 31-24, 12-16, 24-20, 16-19, 20-16, 4-8, 16-12, 8-11, 12-8, 11-15, 8-3, 19-24, 28-19, 15-24, 3-8, 2-7, 8-12, 24-27 (not 7-11, 22-18!, as white will win), 12-16, 27-31, 16-19, 7-11, 19-15, 10-19, 17-10, 31-27, 10-6, 27-23, 6-1, 19-24, 21-17, 23-26, 25-21, 26-30, 1-6, 11-15, 6-10, 15-19. Wm. F. Ryan.

O---11-20, 19-16, 12-28, 30-26, 10-19, 17-1* is no better, and also loses. The important point is to take the stroke into square one, and not to three, as the ending with the king on square three cannot be scientifically won.

P---White now has a free hand with his king. Black cannot crack the line without the loss of a piece, and subsequently loses because his position deteriorates. Although the stroke following black's 15-18 move at JV has been published several times, I can find no record of it being properly executed. Invariably, white has made the mistake of jumping into square 3 at Note P. I make no claim for the play prior to the shot, but its proper execution, as revealed in this study, as well as its attending formational structures discussed in the notes, are my contributions to an outstanding, brilliant, and practical stroke."

1---30-25 is substantially better here---Ed.

2---4-8 would have been preferable---Ed.

3---While 3-8 can't be called "winning" it certainly gives Black an edge---Ed.

4---Willie's comment is hard to understand as the computer finds this position to be dead even. Perhaps White is stronger in practical over the board play.

5---Why Willie stars this move baffles us; far from winning, it gives Black the advantage! 32-28 was the right move here---Ed.

6---This is not actually a losing move---Ed.

7---8-11 is best; White now has a solid edge---Ed.

8---While White can't be said to have a clear win, 24-20 was correct here. The game is now a draw.---Ed.

9---The game is definitely a draw according to the computer; we don't see Willy's win for White at all---Ed.

Can you demonstrate the draw for Black here? Fix the crack in the problem and then click on Read More to check your solution.![]()

A Gentle Stroke

We've often said that stroke problems are not for everyone, but a gentle stroke of the type shown above (yes, we've done this theme before) is pleasing to almost everyone.

The stroke problem below has fewer pieces than is typical for problems of this type, and is in fact quite a lot more gentle than many others. See how fast you can solve it from the diagram, without setting up a board or moving the pieces.

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W7,23,26,27:B6,20,K30,K32.

When you've found the solution, click your mouse (gently, of course) on Read More to verify your answer.![]()

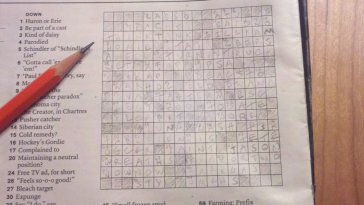

Diagramless

Today's column brings our loyal readers something completely different. Not only do you have to solve a checker problem, you need to figure out what the problem is! It's somewhat analogous to a diagramless crossword, though we see it as considerably easier to solve.

The following verse was published under the title "Puzzle Problem" in The Checkerist in 1887 by our old friend O.H. Richmond, whose work we've featured before. Though we've never found out what the "O.H." in "O.H. Richmond" stands for, "R.A.G." in the poem obviously refers to Robert A. Gurley.

A game of checkers once was played in 1883

Between a man named Robinson and his friend R.A.G.

It was a very pretty game; with neither one ahead.

Until it came quite near the end, when R. A. Gurley said;

"I think I have the best of it, as one can see,

With my two Kings on four and five, and single man on three."

"You may be right," said Robinson, "but I have got the move.

And though my men are single ones, yet tartars they may prove.

But I must move to eleven now, for if to twelve I go,

You catch me in a problem, by Spayth, of Buffalo."

"Ah," said Gurley, "Rob, my boy, that move was very fine.

I fear t'will let that other man from thirteen down to nine.

For if I move my single man, it lets you get a King.

And yours on twenty we'll change off as sure as anything."

The end soon came, Rob drew the game,

But Gurley found next day,

oh, what a sin! he had a win

by a pretty piece of play.

Where's the diagram? Not so fast! There's enough information in the poem to figure out the position and the terms of the problem. You'll need to do that first; if you do, you'll have a nice checker problem to solve.

When you've got it all worked out, just click on Read More to see the problem diagram and the solution.![]()

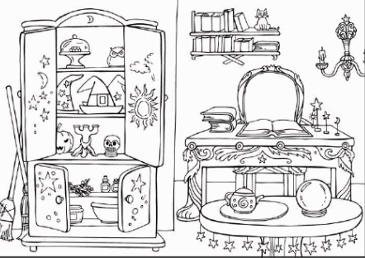

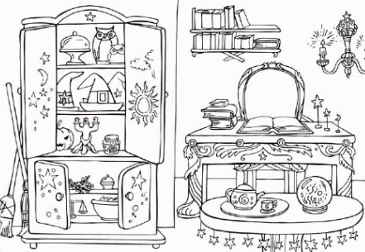

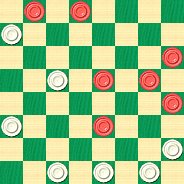

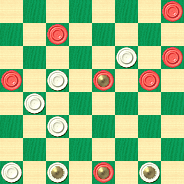

Find the Differences

Yes, we've definitely done this theme before--- Find the Differences, that is--- but with today's Checker School lesson, it certainly bears repetition.

Much as the drawings above have subtle but important differences--- 17 of them, we're told--- the two checker positions below similarly have two small but important differences. Yet both positions yield a White victory, as long as your skills are up to the task.

BLACK

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:WK15,K18,20,K22:B12,K21,K29,K30.

BLACK

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:WK15,K18,K19,20:B12,21,K29,K30.

Can you solve these? Of course, we recommend that you give the checker positions most of your attention, but we have to say the cartoon puzzle is interesting, too. Clicking on Read More will give you the solution to the Wyllie and Spayth problems. We still haven't completely solved the cartoon!![]()

The Kidnapped King

In last month's installment from Willie Ryan's Tricks Traps & Shots of the Checkerboard, Willie told us that one of the moves "sets up a fine problem study by Champion John T. Bradford, American member of the 1927 International Checker Team." But that column had already become rather involved, and so we split off Mr. Bradford's study and present it this month. We think you'll agree that it deserves space of its own.

Black's position in the diagram below looks pretty good. How can White pull this one off?

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W5,14,21,28,30,31,32:B1,2,12,15,16,20,23.

Don't let the apparent difficulty carry you away; with enough effort you can escape with the solution, though it will be a real struggle. When you're ready, click on Read More to see the solution and a full set of explanatory notes.![]()

Fundamentals

One thing experts agree on: if you're going to master something, whether it's playing baseball, writing novels, or becoming a checker champion, you've got to know the fundamentals. In the photo above, an aspiring baseball player is learning the fundamental skill of making contact with the ball.

Our game of checkers has its own fundamental skills, and solving a position like the one below is a definite and required step on the road to excellence.

WHITE

White to Play and Draw

W:W23,31:B2,K22.

Tommy's Big Match

A Middle School in Central Florida

This story continues a series we began in previous columns:

Uncle Ben's Porch: Making Varsity

The final school bell of the day rang and Tommy quickly put his books in his locker and headed for checker team practice. It was Tuesday afternoon and in just a few minutes Tommy would play his big match with Joey Zee. If Tommy could win the match, he'd have a place on his middle school varsity team next year.

Tommy

Joey was not a nice boy, not in the least, and Tommy expected some sort of tricks or antics from him. But all day yesterday and today Joey had been strangely quiet, just smiling slightly if Tommy happened to look his way during class or pass him in the corridor. Tommy didn't know what to make of it. It was very uncharacteristic of Joey. Ordinarily, Joey might have tried to give Tommy a shove in the hallway or make rude faces and gestures during class. But there had been none of that, just a strange and unanticipated calm.

Maybe things will work out, Tommy thought. Maybe Coach Hovmiller has warned Joey enough times that Joey is watching his step, afraid of being put off the team once and for all. Well, thought Tommy, I'll just follow Uncle Ben's advice. I'll concentrate on each move and make it count. I won't think about anything else except the move I have to make.

He was just a corridor or two away from the practice room when his cell phone vibrated. He pulled it from his pocket. It was Tina calling.

Tina was also a member of the junior varsity checker team. Over the past months, she and Tommy had developed a special sort of friendship, the kind that seventh grade girls and boys often do.

Tommy answered the phone. "Tina, you should be in practice now!" he said.

"Tommy, help me!" Tommy, hearing the panic in her voice, felt a cold lump in his stomach.

"Tina, what's wrong?"

"He locked me in the girls' room and I can't get out!"

"Who? What girls' room?"

"That horrible Joey! I was on my way to practice and he was following me, just like he's been doing all day. I went into the girls' room and waited a few minutes, hoping he would just go on to practice, but when I tried to open the door it was locked! Oh, Tommy, please get me out of here!"

"Which girls' room?" Tommy said.

"The one nearest the practice room!"

"OK, OK, hold on, I'm headed in that direction. I'm almost there. Stay calm."

Tommy turned the corner and the girls' room stood in front of him.

"Hang in there, I need to put the phone down." Tommy put his cell phone on the floor and walked up to the door. He could hear Tina pounding on the door from the other side. Tommy tugged on the door handle but it wouldn't budge. It had been double locked and couldn't be opened from either side.

"I'll have to get the janitor," Tommy said through the door. "Just stay calm."

"Hurry!" said Tina, also through the door, her words muffled by the thick wood. "He's turned off the lights and it's pitch dark and I'm scared!"

"I'll be back with help!" said Tommy, and he ran off down the hall, grabbing his cell phone from the floor.

The janitor was hard to find, and it took Tommy a good fifteen minutes to locate him and explain what had happened. The janitor, a short man with graying hair and a scraggly moustache, looked skeptical but went with Tommy back to the girls' room. He unlocked the door and a sobbing Tina emerged.

Tina

"Well, golly gee," the janitor said. "I tink it was dat mean fat kid what done dis, the one allus shneakin' a shmoke. He was hangin' around here. Looked like trouble to me."

"Tommy, your match!" Tina cried.

"Thanks for your help, Mr. Olafsen!" Tommy said, already running down the hall with Tina following.

Mr. Olafsen

"Hey just a minute you kids--- oh, never mind, I gonna find dat fat kid what did it."

Tommy didn't hear the rest of it. He burst into the practice room. Of course, the matches had long since started. And there was Joey, sitting at his checkerboard, with a smug, self-satisfied smirk on his face.

"Why, you---" Tommy shouted.

"QUIET!" Coach Hovmiller's powerful voice silenced Tommy at once. "I won't have a disturbance while games are going on! You are very late, Mr. Tommy Wagner, and you'd better sit down and play at once!"

Joey must have started Tommy's clock right on the dot of three-fifteen, the assigned time for the match. It was now three forty. Twenty-five minutes had already elapsed, and the game time was set at thirty minutes per side.

That meant that Tommy would have just five minutes to make all of his moves in the game, while Joey would have thirty. Joey had a huge advantage, and he knew it.

"You did this on purpose," Tommy hissed as he sat down at the board.

"Better get cracking, goody two-shoes," Joey whispered back. "Spent a little too much time in the restroom with sweetie, did ya!"

Joey

Tima was still trying to control her crying, sitting on a bench on one side of the room. It was all too much for Tommy. He just wanted to pummel Joey's face with his fists, even though that would be suicide for his checker career. He was half out of his seat when he saw Tina look over at him and shake her head. Then she started crying again and fled for the door before Coach Hovmiller could scold her.

Tommy took a deep breath and sat back down. Even though the clock was still running. he closed his eyes, shut out Joey's whispered taunts, and took deep, calming breaths. When he opened his eyes again, there were only four minutes left on his clock, but there was a steely look of determination on his face that announced that the game was far from over. Joey stopped whispering and turned his gaze away, obviously frightened. Like most bullies, he was a coward, and whatever he saw in Tommy's face gave him quite a scare.

Joey had Black and had already moved. Tommy made his reply and the game began to play out. Were Joey's hands shaking just a little when he moved his pieces? Perhaps so, but Tommy kept his focus on the board and the position, making his own moves quickly because he had little choice in the matter.

Some time passed. Joey still had 15 minutes left on his clock but Tommy only had two. It was Tommy's move and the position was like this.

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:WK32,K30,29,22,17,14,11:BK31,16,K15,13,12,6,4.

Joey thought he had an easy draw, maybe even a win if he could get Tommy to let his time run out. But Tommy thought he saw something familiar in the position; all those Saturday mornings spent studying with Uncle Ben had taught him a great deal. In short, he knew he might have a win, but he didn't have much time to figure it out. He'd have to think fast.

Tommy was right, there is a win here for White. Can you find it? We won't insist that you do it in under two minutes, but see if you can find it. Then click Read More to see the solution and the conclusion to our story.![]()

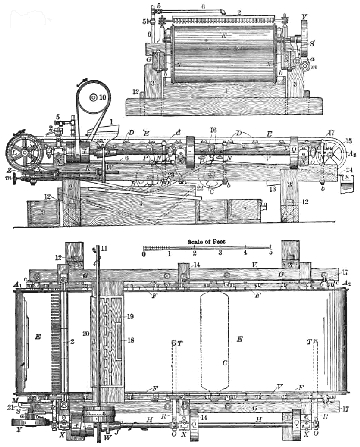

The Frue Vanner Machine

We're going to guess that very few if any of our loyal readers have ever heard of the Vanning process or the Frue Vanner machine, unless one of you happens to be a miner or mining historian. Vanning is a means of separating ore, and the Frue Vanner machine automates that process. It was invented in 1874 by a Canadian mine superintendent with the unsurprising name of W. B. Frue.

Did Mr. Frue play checkers? Perhaps. But his contemporary, one T. Vanner, certainly did, and is credited with correctly solving today's problem position, which is part of our ongoing Checker School series.

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W28,23,22,21:B14,13,11,5.

We won't say that this is an especially difficult problem, and mining for the solution will be like we suppose real-life mining to be at times: long and tedious and requiring care and caution. So dig deep for the winning method, and when you've extracted it, shovel your mouse to Read More to see the solution, sample games, and detailed notes.![]()

Sturges Steamroller

You wouldn't want to get in the way of the powerful looking machine shown above; it's something not to be tangled with. But today's entry from Willie Ryan's Tricks Traps & Shots of the Checkerboard is both powerful and tangled. It's a complex situation with quite a fine solution. Willie has a lot to say about it; take the time to play through the notes and variations to enhance your understanding and enjoyment of this one. With the help of modern computer analysis, we've added even more notes of our own.

| 11-15 | 16-20 | 8-11 |

| 23-18 | 24-19 | 29-25---C |

| 8-11 | 7-16 | 10-14---2 |

| 27-23 | 22-18 | 19-15---3 |

| 11-16---A | 4-8 | 3-8 |

| 18-11 | 25-22---B | 22-17---U. |

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W32,31,30,28,26,25,23,21,18,17,15:B20,16,14,12,11,9,8,6,5,2,1.

"At this point, white has fallen into a hoary snare, first shown by Joshua Sturges in 1800, which has been victimizing the innocents since its inception. The diagram shows the position after white's fateful faux pas."

A---With this move, black inaugurates the Slip Cross opening, one-time favorite of go-as-you-please players. Although white seems to have the upper hand on most variations of play, black's winning chances are by no means meager.

B---The only fertile move at this stage. If white takes 31-27, black can force a draw as follows: 31-27, 9-14, 18-9, 5-14, 25-22, 8-11, 28-24, 3-7, 22-18, 1-5, 18-9, 5-14, 26-22, 11-15, 22-17, 7-11*, 29-25, 6-9*, 17-13, 14-18*, 13-6, 2-9, 23-5, 16-23, 27-18, 20-27, 32-23, 15-29. J. Tonar.

C---In recent years, the prescribed move has been worn thin by wide and constant usage, and it is now being replaced by the lesser known 22-17---1, as follows:

| 22-17 | 5-14 | 18-9 | 2-7---F | 23-16 |

| 10-14---D | 29-25---E | 5-14 | 22-18 | 12-19 |

| 17-10 | 3-7 | 26-22 | 14-17 | 18-14 |

| 6-24 | 25-22 | 11-15 | 21-14 | 19-23---G, |

| 28-19 | 7-10 | 32-28 | 10-17 | ending in a |

| 9-14 | 22-18 | 15-24 | 19-15 | draw. |

| 18-9 | 1-5 | 28-19 | 16-19 | Frank Dunne. |

D---The great Frank Dunne, "King Kong" of yesteryear's draughts scribes, was the first to show play on this reduction, which at once throttles all threats by white. The move most frequently taken here is 9-14, although it is not so good as Dunne's 10-14 trouble eliminator. All the major points of the 9-14 line are outlined in the following play:

| 9-14 | 17-14 | 10-15 | 21-17 | 23-30 |

| 18-9 | 10-17 | 18-14 | 16-19 | 32-7; |

| 6-22---H | 21-5 | 15-18*---M | 10-7 | drawn. |

| 26-17 | 3-7 | 14-10 | 2-11 | Wm. F. |

| 5-9---K | 29-25 | 11-15* | 27-24 | Ryan. |

| 23-18---L | 7-10 | 31-27 | 20-27 | |

| 16-23 | 25-21 | 12-16* | 30-26 | |

E---White does not have any alternative play here worthy of mention. If he tries 26-22, then the countering play will be: 3-7, 29-25, 7-10, 22-18, 1-5, 18-9, 5-14, 25-22, and we are back to Note C, on the seventeenth move.

F---Another way to draw here is by: 20-24, 22-18, 24-28, 18-9, 28-32, 21-17, 32-28, 31-27, 2-7, 9-6, 7-11, 6-2, 11-15, 27-24, 16-20. Wm. F. Ryan.

G---Black has virtually forced the draw all the way from Note D (10-14). This is big league analysis.

H---Black is not really pinched here. The center jump also produces the draw; viz: 5-14, 29-25, 3-7*---I, 25-22, 11-15, 17-13, 15-24, 28-19, 14-17*, 21-14, 10-17, 22-18, 20-24, 18-15, 16-20, 19-16, 12-19, 23-16, 24-27, 32-23, 6-9, 13-6, 1-19. P. H. Ketchum vs. J. H. Scott.

I---A vital point in the defense. If 11-15 is tried, a draw by black is doubtful against the following play: 25-22, 15-24, 28-19, 20-24---J, 19-15, 10-19, 17-10, 6-15, 23-18, 24-27, 32-23.

J---A player by the name of J. S. Heyes attempted to show a draw here by 3-8, 17-13, 8-11, 22-18, 1-5, 18-9, 5-14, 26-22, 20-24, 22-18, 6-9, 13-6, 2-9, 31-26, 24-28, 26-22, 9-13, 18-9, 11-15, 9-6, 15-24; at this point Heyes recommended 23-18, which allows black to draw neatly by 24-27 etc.; but if instead of 23-18, you play 6-2, the win becomes obvious.

K---Several authors have claimed that this move is a losing one; but it may be played to a draw without exertion. At K, black can also draw by 3-7, 17-14 (if 29-25, 5-9, 23-18 are moved, Note D will apply), 10-17, 21-14, 1-6, 29-25, 6-9, 31-27, 9-18, 23-14, 16-23, 27-18, 11-16, 25-22, 20-24, 28-19, 16-23, 14-9, 5-14, 18-9, 7-11, 22-17, 11-15, 17-13, 15-19, 9-6, 2-9, 13-6, 12-16. A. E. Greenwood.

L---If 29-25 is played, then the draw comes about with: 9-14, 17-13, 3-7, 13-9, 11-15, 25-22, 15-24, 28-19, 7-11, 22-18, 20-24, 9-5, 16-20, 18-9, 24-27, 31-24, 20-27, 23-18, 27-31, 21-17, 11-16, 18-15, 16-23, 15-6, 1-10, 5-1, 10-15. Wm. F. Ryan.

M---The only move to draw. 11-16 loses and sets up a fine problem study by Champion John T. Bradford, American member of the 1927 International Checker Team. We illustrate the position (after 11-16) with a diagram on the next page---**."

U---The loser."

1---The computer, by a very slim margin, seems to still prefer 29-25, but Willie is talking about practical over-the-board play and not deep computer analysis---Ed.

2---The computer shows that Black has gone seriously astray here; 3-8 would have been correct---Ed.

3---31-27 was best to retain White's lead. This allows Black to get back in the game, but it took some extensive computer analysis to come up with this conclusion---Ed.

**---This will be the subject of next month's installment---Ed.

Willie made a couple of errors here, but it's hard to fault him. As the notes show, this particular run-up illustrates the difference between practical play over the board and detailed and often arcane computer analysis. In the end, checkers is intended for humans! In any case, can you find the win? Can you correct the play at Note U and find the drawing line?

Don't let our double challenge steamroller you. Solve the problem and then roll your mouse over to Read More to see the solutions.![]()

The Checker Maven is produced at editorial offices in Honolulu, Hawai`i, as a completely non-commercial public service from which no profit is obtained or sought. Original material is Copyright © 2004-2025 Avi Gobbler Publishing. Other material is public domain, as attributed, or licensed under Creative Commons. Information presented on this site is offered as-is, at no cost, and bears no express or implied warranty as to accuracy or usability. You agree that you use such information entirely at your own risk. No liabilities of any kind under any legal theory whatsoever are accepted. The Checker Maven is dedicated to the memory of Mr. Bob Newell, Sr.