Chess, Checkers, and Go: A Short Comparison

Editor's Note: We intend, at some point, to add a Xiang Qi section to this article.

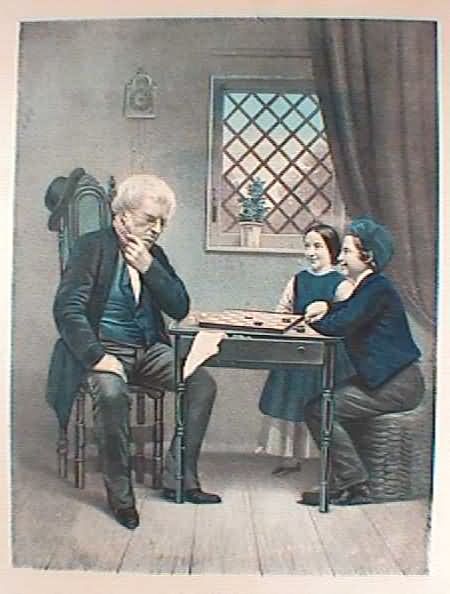

I've been an on-and-off fan of abstract strategy games for as long as I can remember. My father, of blessed memory, taught me to play checkers when I was three or four years old. I learned chess at about age six. I didn't discover Go until graduate school.

I played chess pretty seriously during high school but ran out of spare time in college. Recently, as is obvious from this web site, I've taken a real interest in checkers. And, I've spent some time at Go a little while back.

So inevitably someone asks the age-old, hackneyed questions:

- Which game is best?

- Which game is hardest?

- Which game requires the most skill?

These are questions without answers. Each game is very different, one from the other, and each game has its own strong points. They are all the best, they all require a great deal of skill to play at an expert level, and they are all "hard" in a certain sense. Let's have a look.

Checkers has the easiest rules to learn. There are but a few. There are only two kinds of pieces and movement and capture is nearly uniform. The game's objective is easily expressed and easily understood: if you can't move, you lose.

Go probably is next easiest in terms of rules. Placing stones and capture is learned very quickly. The idea of "liberties" takes a bit of understanding, especially the idea of chains of stones and the liberties shared by a chain. But it still isn't very hard. The game's objective is easily expressed, but scoring is not really all that simple, especially given the myriad rule sets for scoring. (Chinese scoring is probably the easiest to grasp at first; Japanese scoring is a bit harder.) All in all, the game is relatively easy to learn but less so than checkers.

Chess is harder because there are many different types of movement and three kinds of capture (counting en passant separately). There are a few movement exceptions (e.g. castling) that need to be learned. The objective of the game, to capture the king, is easily expressed and understood. But overall, I'd have to say that chess has the most complex rules and likely takes the longest to learn the mechanics of play.

Checker and chess play is that of reduction: as the game continues the number of pieces decreases from an initial maximum or full setup. By contrast, Go is a game of accretion; it starts with an empty board and the number of stones on the board increases more or less steadily through the end of the game (with minor fallbacks for infrequent large captures).

Calculations as to move permutations will likely show checkers lowest, chess next, and Go after that. I base this on a simple observation: checkers has 32 playing squares and 24 pieces; chess has 64 playing squares and 32 pieces; Go has 361 playing points and up to an equal number of stones.

But in all cases the numbers are large enough to be effectively unlimited in human terms. So instead let's look at how the games are played in practice, with a very revealing note about computer play.

Checkers has been analyzed a great deal over the decades in terms of opening moves and opening move combinations. It is safe to say that these are reasonably well understood for the most part (with notable and very interesting exceptions). To some degree, computer analysis has really accelerated a more complete understand of checkers opening play. The number of opening lines is understandably fewer than in chess, where much analysis has also taken place and the published literature is phenomenal in volume.

In over the board play at a master level, a very good understanding of opening lines in both chess and checkers is an absolute requirement. At a less than master level, a good understanding is useful, more so, it seems, in chess than in checkers. In this respect, we'd say checkers is "simpler" because there are fewer opening lines to learn about.

Go is another matter. There are certainly opening patterns that need to be understood, but the whole feel is different. There isn't the same notion of "the 9-14 variation of the Ipswich" or "the Impossible variation of the King's Gambit Accepted." Go has patterns (joseki) and tactics (fuseki) that need to be learned, but it isn't quite the same.

Does this mean that Go is simpler? Certainly not. The variety of possibilities is so large that deep conceptual understanding is vital. And achieving that depth of understanding takes much time, study, and practice.

What does all of this say about play depth? Checkers has been characterized as narrow and deep; chess as broad and deep; and Go has a depth of its own, very different from checkers or chess. All three games have enough depth of play to last a lifetime. My own experience tells me that checkers is amenable to focused study; chess requires broader study due to increased "width"; while Go requires much patience and dedication.

This is borne out by the relative success of computer programs to play these games. Checkers programs have become extremely strong and play at the very highest levels of skill, and may in fact be the equal or near-equal of the best human players. Chess programs are likewise quite strong, but, despite the celebrated success of "Big Blue" aren't generally as good as the best human players. Go programs are another matter; the best of these is maybe as good as an intermediate human player, but no better. Go playing programs are very far from a master level of play.

This tells us two things: first, there is the obvious statement about depth of play, at least based on permutations of possible positions and moves. Second, it tells us that Go is more about global understanding and comprehension than it is about pure calculation; and this is probably why Go mastery seems (prodigies excepted) to be a longer-term affair than mastery of checkers or chess.

But let's address a final question, a more meaningful variation of "which game is best," and that is:

Which game do I like the most?

I can immediately say that, having once played chess seriously at a lower intermediate level of skill, I dropped out literally for decades, and only recently returned to competitive play. It had become hard work instead of pleasure. I had reached a point at which lots of study of opening lines was really necessary to move to a higher level, and, frankly, I didn't want to do it. Now, upon returning after such a long absence, I've learned how to balance my approach so that it's still fun. But I doubt I will rise above the intermediate category unless I devote a lot more time to the game.

I've only relatively recently begun serious checker play, and I'm still at a fairly low skill level. But I enjoy it immensely. I appreciate the economy of the rule set and game principles. While I need to study some opening theory, I'm not at a level where it's become so vital that it's a job or a chore in itself. And there's a certain nostalgia: it's a grand old game, one I learned from my father, and I think I honor his memory by keeping it up. It also requires less time to play a single game than chess or go, and given a busy life with limited spare time, this is no small matter.

Consider this: I might have an hour or so each evening to spend on-line, sometimes a little more, often less. A game of Go on a 19x19 board will take over an hour, maybe as much as 90 minutes. A game of chess is over half an hour, maybe even as long as an hour. A game of checkers is more like 15 minutes or less. It really makes a difference.

Go, for me, is a long-term project. It's fun to read books, solve problems from Go problem books, and build my knowledge slowly. But it takes too much time to quickly take the plunge. Games are long; there is much to learn; and I must be patient. I think Go will be a continued interest, but it will take a back seat to checkers.

Bob Newell, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA: last revision 14 April 2006.