Learning Checkers

wherein is contained & revealed

THE SECRET TO CHECKERS SUCCESS

being a new & innovative modern method

for the rapid improvement of the tyro

THIS ARTICLE IS IN THE PROCESS OF REWRITE!

It currently contains a mix of new and obsolete info. I hope to have it fully rewritten Real Soon Now.

(The impatient should jump ahead to section 4.1).

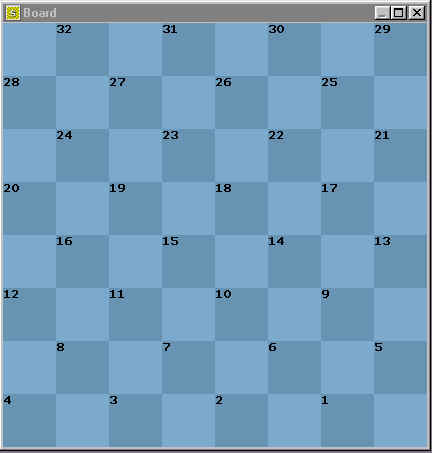

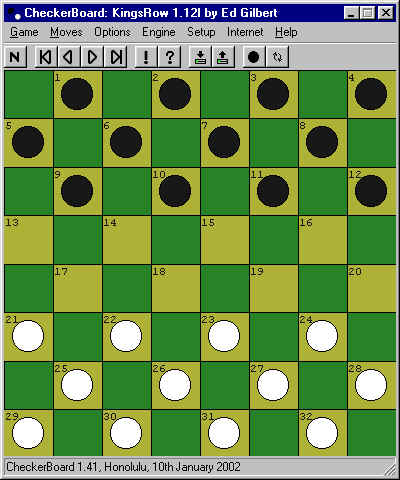

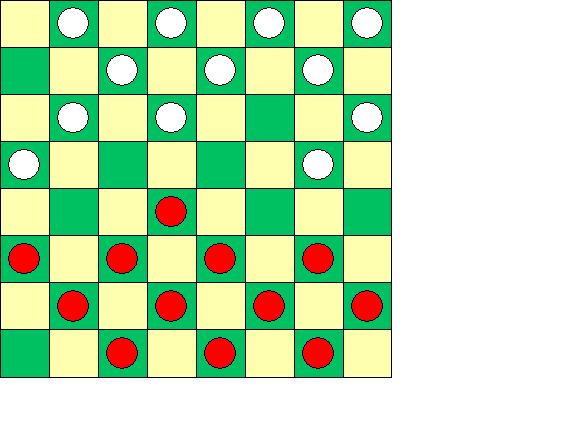

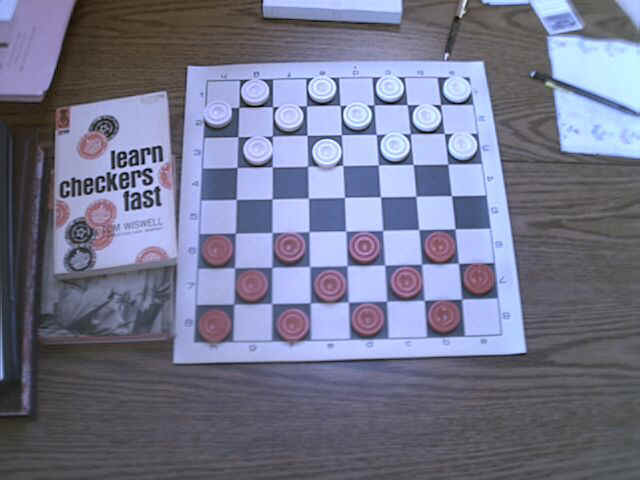

1. What's Out There Already There are many great internet sites loaded with information about checkers and links to learning material. I'll just mention two of them here: My own Checker Maven site: http://www.checkermaven.com and The American Checker Federation: http://www.usacheckers.com If you learn everything on my site, you'll already be at master level, while the ACF site has various tutorials and much more. 2. A Simple Approach I don't wish to duplicate what's already available, and in any case I'm not a very skilled player myself. But I'm improving rather rapidly, and I'd like to tell you how I'm doing so. The best approach for you may be different; you'll have to be the judge. It's simple. There are two components to learning: It's as basic as that, so let's look at how to go about these two learning tasks. 3. Study To do some real study, you'll need a physical checkers set (see my companion article, Buying A Regulation Checkers Set , and Appendix E below). Set this up somewhere in a place where it can be left undisturbed, but where it will call out to you each time you pass it by. I prefer a set a bit smaller than regulation size for study purposes. One other possibility for limited space environments is a magnetic set that can be put on a shelf or the top of the cabinet without disturbing the position of the pieces. There are lots and lots of these available on-line so I'll leave that part up to you. Also consider one of the really little portables; more about that later. You'll also need some good study material. A considerable amount can be found on-line through the web sites mentioned; my site has a large number of free books, including the one you need the most, Checkers for the Novice by Richard Pask. Other books you should download from my site are Checkers Made Easy and The Clapham Common Draughts Book. One to search for from online booksellers is Robert Pike's The Little Giant Encyclopedia of Checker Puzzles. Richard Pask's book is the best book for the serious beginner ever published. It requires work and dedication, but it covers everything you need to know to go from complete novice to the upper 1% of checker players (not an exaggeration). It will put you on the path to becoming an expert. Checkers Made Easy and The Clapham Common Draughts Book are all about tactics, and tactics are what you need to learn first, and learn them inside and out. When you've mastered these books, start using the Checker Cruncher website. It's a checker tactics server and will challenge you with thousands of checker problems. And finally, Pike's book is a nice, portable collection of tactics problems to work on in odd moments in odd places. I've just outlined at least a year of study, probably more. Later on, and by no means should it be right away, you'll want some other books. Richard Pask is continuing his Logical Checkers series, and that's the first place to look (free downloads on my site). When you get even further along, look for Ben Boland's books, such as Familiar Themes and Famous Positions. But as wonderful as these books are you won't need them for some little while. Now that you have your set ready, and some books at hand, the first thing to do is to learn the move notation. This is well described in the books and on the internet, so I won't repeat it. I'll just add my own view: While you can number your study board with little stickies and the like, I think it's worth taking the time to master the square numbers. This takes a little time and concentration but is worth the effort, and allows you to visualize moves and sequences away from your board and in other environments when those little stickies won't be there. Here's what you do. Working from one of those books, play through some of the sequences or games in them. Stop to count out the square numbers, referring back to a numbered diagram only when necessary. Play through the moves. You will inevitably make some mistakes; that's OK. Just go back and start over. The repetition will help. Then turn the board around and play over the same game or sequence from the other side. Get used to the square numbers from both orientations. I've found that about a week or so of this, while admittedly frustrating at times, pays great dividends and soon "11-15" will have instant recognition for you. You'll be able to clearly picture the move in your mind and on the board. So then, what do you study? I'd say just work straight through the books you choose (but see below). Make sure you play plenty of games in-between study sessions, and don't worry about losing; you're learning. As you play more games and have more questions, go to the relevant sections of the books and work there. Work a lot on tactics. A player such as myself loses quickly through blunders. Studying various shots and traps help you recognize dangerous situations and avoid some of the worst errors. Work on endgames will help you learn a lot about how pieces work together. Learn how two kings defeat one. (I watched an on-line game recently in which a fairly high-rated player could not solve this elementary ending.) Learn how three kings defeat two. Learn the basic endgame positions. Work through them over and over until you really know them. (I'm not there yet either.) Pask's first book will get you into the openings, at least the basics (see Appendix below for more discussion of this controversial question). Even if you've learned to avoid blunders, an expert player will get you into a losing opening line and it's all downhill from there. Learn something about the major opening lines and replies. After you've played a game and gotten into trouble, go back and look up that opening and gain a little more understanding. Playing through main-lines and variations can be confusing. A second set, such as the small magnetic set described below, is helpful. Keep the main-line on the main board, and play through the variations on the small set. 4. Play Derek Oldbury said it best, "If you don't want to lose, don't play." There are several forms of play: Internet play against live opponents, face to face play against live opponents, correspondence play, etc.; and play against a computer. I'm going to reveal the Secret to Checkers Success in the next few paragraphs, so pay attention. 4.1 Play Against the Computer Get yourself a good computer checkers program. The only real choice today is CheckerBoard with the KingsRow engine. See Ed Gilbert's site. But now I shall reveal all. When I first got on-line I got destroyed in live games. I had no idea what I was doing. I blundered games away before they could even be won by my opponent through superior play. But this has changed. Although I still don't consider myself a good player (mostly because I'm not), my rating is rising and I am winning games from players who I thought by rights would wipe me off the board. It's because I started playing computer games, and playing them in a certain way, and combining this with a certain type of book study. You want to play against such a strong program that you have no chance. You really do. When playing the computer, take time with your moves, really think about them, and learn to avoid game-costing blunders (throwing away a piece, missing a simple shot, etc.). That's one thing about computer play; there is no one to keep waiting on the other end and you can take twenty minutes on a move if you wish. Your practice games against the computer should be hard games. If you do the typical click-click-whatever and don't think and calculate, then go play solitaire instead, as you're wasting your tme. Inevitably, you will fall into a position where you lose a piece or the computer gets you in some sort of shot. That's OK. Now, using the move review features, back up the game and try to see where you started to get into trouble. Often it's just a move or two back; you set yourself up for a trivial two for one shot or exposed a piece fatally. Sometimes you have to go further back, but figure out what went wrong and what a better move might have been. Then make the better move and see how things go. You are not "cheating" as this is not a game played for a win; it's a game played to learn. Every time you get into trouble, back up the game and look for something better. Eventually, of course, you'll reach an irredeemable situation. Now it's time to go back to the beginning of the game to work through it, looking for moves that weakened your position in such a way that you reached a loss. This is easier than it sounds, even for an inexperienced player. Of course this doesn't always work, and at times you need to go back to your books and review the opening line that you pursued. (Programs which show their opening book as the game progresses are helpful for this.) Often you have subtly gone wrong dozens of moves back and it's hard to correct that. But you still can see the type of weaknesses and the losing position that eventually arises and that will be very valuable when playing a mere mortal. I'll say it again: these games are hard work. If they are not hard work, you need to work harder! It's worth repeating: take time with each move. Don't just click around. Think, think, think some more. Play a lot of computer games in this manner, and I can guarantee you will "see" things much, much more effectively when you are playing live opponents. You will blunder far less often (not never) and fall for far fewer traps. Eventually you will gain an understanding of weak and strong positions (the light is starting to go on for me now, I just have to learn to avoid all those weak ones!). This is by far the most effective means of improving your checkers skill I can imagine, at least at the beginner level. I have never seen this method published before, so here it is! Your mileage will vary, but I'll bet it works for you too. There are inherent limitations in what I suggest. But right now I'm playing at a rather modest 1350 or so rating level, and I'm benefiting immensely from computer play. The major limitation will be that while you are learning how to avoid loss, how to avoid bad moves and bad formations, you really aren't aren't learning a lot about winning (except to the extent that you can profit from the other guy's bad position in live play, a bad position which you have learned to recognize from the losing side). Plenty of live play needs to go along with your computer play. An additional note: I feel there is limited use in playing against the computer with the computer set at such a low level that you might win. At low levels the computer just makes plain old dumb moves. While this might make you feel better, it won't really show you how to take advantage of mistakes or weaknesses of the type that you would usually encounter in a live game. Why does this method pay back so richly? Because at the beginner level games are almost always lost instead of won. You must learn how not to lose by throwing away men carelessly, by failing to see the simple shots, by being unware of what's going on. Playing the computer, and replaying moves that lose, will show you clearly and at once what you've done wrong or what you've missed in terms of simple blunders or sheer unawareness.

My method also seems to work at a further stage of development, as you start to approach "advanced" beginner. Now you're (mostly) not losing by dumb mistakes, but (mostly) ending up somewhere in the middle game with a losing position. Again, backing up and replaying almost always shows you something. How did that bad formation arise? Why did you run out of moves?

4.2 Live Play Get on a decent game site like PlayOK (see my companion page for ideas), and play a lot of live games. Try to find an area free of annoying kids who just want to chat, or in the other extreme, play only useless and damaging one-minute speed games. There is a terrible tendency to play too fast on-line, throwing pieces around and not thinking about your moves. You may have to look around, but there are many good games out there to be found. After a game, I like to go back and book in hand take a look at the opening line (some computer programs help with this too). What line did you play? How did you play it? What other ideas are there? If you lost where did you go wrong? Track your progress. This doesn't mean you should fall in love with, or worry about, your rating on sites that give you numerical ratings. Play a lot and see if you feel better about your play. If your rating is 2500, cool. If it's 1050, so what. It's supposed to be fun. Always ask these two questions: If you can't answer "yes" to both of these, especially the second question, you've missed the point. If you are interspersing serious computer play and study, you will find your live play improving. I certainly am seeing that. (But don't get overconfident. After defeating a 1500 rated player, which I couldn't believe I did, I quickly got knocked off by a 14 year old who really wanted a chat session instead of a game. A little humility is often a good thing.) 4.3 Correspondence-Style Play In contrast to the type of head-to-head, live on-line or in-person play described above (also called "over the board" play), correspondence play is modeled after the old and venerable post-card method. The way this used to be done (and in some circles still is) is that you write your move on a postcard, put it in the mail (snail mail), and wait for your opponent to send a reply in the same manner. You'd keep a board or boards handy with each of your correspondence games set up. Today, a few internet sites (see my separate article about game sites) offer a modern and I think much improved option. Unless you live in the darkest heart of darkness, with no internet access, it's the way to go. The on-line sites track your games, e-mail you when it's your turn to move, and provide generally useful displays and tools for play. What you need to keep in mind is that this style of play is very different than face-to-face. In fact, I'd suggest you wait until you're at least out of the beginning beginner stage to tackle this play style. The reason is that in this type of play, use of reference books is allowed, and many hours can be spent on a single move. (Some highly advanced players take up to 8 hours of study for each move!) Use of computers is generally not permitted, on the honor system, and I think that's a good thing, so please don't cheat; it's pointless. So, if you're not at a stage in your development where poring through opening books (and you'll need to have them) is something with which you have a level of comfort, you might want to delay your correspondence checkers debut for a little while. But when you're ready, this type of play is also a great skill-builder, as you'll be doing serious study and reflection for each of your moves. Appendix: Should a Beginner Study Openings? Most of the advice I read from people who know what they are doing (including a former World Champion) recommend that beginners don't study openings; in fact some of them say beginners should not be allowed to even touch an opening book! Now, I think I understand the reasons behind these statements, and I, with little skill and no stature, should not presume to challenge the masters. But let me offer a little different point of view. The problem with studying openings at an early stage is in trying to learn by rote, without understanding reasons and whys and wherefores. Grabbing an opening book and mechanically playing through a number of lines will be confusing and time not well spent. Memorizing lines will prove fatal once your opponent makes the "wrong" move and you're then on your own in uncharted territory. So, I must agree with the authorities, that opening books can cause a lot of harm or at best much wasted time. But my alternative view stems from this: those same masters will say that most games are lost in the opening! So what is the poor beginner to do? I think the answer is not so difficult, and it relates to the method of play against the computer that I recommended above. Certainly, you don't grab Lee's Guide and start at page one and work forward. But you need at least a clue. Pask's first book will give you the basic ideas and a simple but workable repertoire. The more complex stuff can come a lot later. I think a beginner should do the following: for live games (or even computer games), play through the game over the board as always. Then, you can go back and try to understand the opening line. What are the results? Did you get cramped or in some kind of bind? Did you lose men due to a trap or shot? What isn't clear to you? At that point, getting out an opening book or guide will be helpful rather than harmful. Where does "normal" play deviate from what you did, and most importantly, why? Now, you don't just memorize the "normal" line at this point. Your job is to try to figure out why the "normal" moves are better than the ones you chose. Attempt to work out the reasons and principles behind the moves. Am I right about my approach? I think overall you must learn at least something about openings, but if you approach it from the standpoint of "What are the principles" and "Where did I go wrong" you will get maximum benefit and avoid the downsides that the masters warn about. Let me close with a specific example, which you can readily ignore if you've not yet learned move notation. I played Red in an online game and opened with 11-15. The reply was 20-24, the "Ayrshire Lassie" opening. The game continued with 8-11, 28-24, 4-8, 22-17. So far so good, but after this somehow I managed to get my single corner completely tied down. I'll spare you the details, but I should have lost and it was just luck that I didn't. A glance at an opening book quickly showed me where I went wrong. I learned the principle rather than memorizing the moves. I think this subject is so important that I've put together this detailed example to further illustrate the point. Appendix E: Some Nice Checker Sets for Study Purposes There are two types of sets to be considered: Normal table sets and portable sets. There is a lot of ground to cover here so I'll just describe the sets I currently use. I won't repeat all the vendor information that is on my companion page about buying a regulation checkers set: checker-sets.html . As I mentioned above, for a table set for study, I actually like something smaller than a regulation set. At the moment I'm using 1 1/4" red and white checkers and a "small" vinyl board with green and white squares (about 1 1/2" on a side) from It's Your Move Chess and Games. The total cost of these is about $22 plus shipping. (The photo below doesn't show the true green of the squares.) There are many magnetic sets, but I have yet to find a good large sized one. All of them seem to have terrible square coloring, with the black squares so dark you can barely use the set except in full sunlight. Instead, I'm using a small portable maybe a third larger than a CD case, from Kling Magnetics . The board and piece colors are funky, to say the least, but the set is highly usable; in fact you can set up a position, close the case, and expect to find the position still there when you return to it. This set is also something that is good for use during downtime such as waiting (where else) at the doctor's office. At $6.50 including shipping this is a remarkable bargain. (Note: The board is rotated 90 degrees with a dark square at the right instead of a light square. The company says they will correct this next printing, but it really doesn't matter that much. As another aside, they sell a giant magnetic checkers wallboard and pieces, with proper orientation and colors, for a lot less than you would expect to pay. This would be suitable for clubs or classes.) Disclaimer. You get what you pay for, and you know all about free advice. I am a lower end player myself, and I have described books, equipment, and study techniques that I am finding useful. I do not claim or pretend to be an expert, and none of my remarks should be interpreted in that light. If you don't like what I have to say, don't agree, or have better ideas, by all means write. I do not represent any company or specifically endorse or warranty any products described here. You must make your own evaluation in your own environment. A Few Reflections. A really long time ago I was a serious chess player of middling skill. But back then, if you wanted a game, you had to find a player. I played with the kids in the neighborhood and maybe Wednesday nights at the town's chess club. That was pretty much it; during the school year there was a high school club and so we all played each other a couple of days a week after school. What is different today, and which changes things to an immense degree, is the availability of on-line play and the possibility of play against the computer. On-line play pretty much means a game whenever you want one, against a wide variety of styles and skills. And, the great utility of play against the computer has been discussed above. The bottom line for me is that I think I've learned more checkers in the past month or two than the amount of chess I learned in a couple of years way back when. I've gotten to the 1350 or so checkers rating level in about two months; at chess I was maybe 1600 at my absolute best ever. (And I seem to be stuck at right aroung 1460, or even a little less, because my free time for playing has decreased very much. You can't learn if you don't play! But as I said above, the rating isn't the point. It's what you learn and how much enjoyment you get.) The overall effect of this on checkers would seem to be two-fold. First, there should be many more checker players. Second, they should be of higher skill and should develop a lot faster. Is this actually the case? I'm pretty sure that the second part, about higher skill and faster development, is true. I'm told that the first part, about more players, isn't necessarily true. I'm not so sure, though. At any given moment several dozen serious checker players seem to be on line. I find that impressive. Further reflection: I think when I first wrote this article, I didn't stress "live" or on-line play quite enough; in fact, my main learning impediment at the moment is not lack of study so much as lack of enough time to play a lot of games against live opponents. I'd think half a dozen good games a day, every day, might be an ideal number, although for those with busy lives, perhaps hard to achieve. Any thoughts of your own? Comments? Reactions? Suggestions? Please write bobnewell@bobnewell.net