The Checker Maven

Jump to navigationMemory Troubles: A Checker School Installment

In our ongoing Checker School series, we've been following along in Andrew J. Banks eclectic 1945 book Checker Board Strategy. Today we come to a set of articles on the topic of memorization. In our picture above, the protagonist is evidently trying to memorize a list of words. Of course today we know of many systems to aid in memorization, but the question of course is, what role does memorization play in our game of checkers? In Mr. Banks' first segment, he talks about repetition. Let's hear what he has to say.

"I am a bookworm," chuckled Hatley, "I will memorize everything." It was during his February vacation in Florida when he started to study "Lees' Guide." In his room and on the white sands of Daytona Beach, he memorized game after game, but when he returned to the Nation's Capital, he discovered that Stone did not play those games. Hatley soon forgot them; hence he was completely discouraged. What was his mistake?

He had violated the rule of repetition; he had tried to memorize too many games at one time. Natural--- but incorrect! He should have selected fewer games, then repeated them from memory not only on the first day, but on the second, third, fourth, seventh, and eleventh days also. To see what it was that he had forgotten, he should have tested his memory immediately, then again and again on later days until he could follow the sequence of cause and effect through each game and some of its variations. Remembering is aided by repetition and spacing periods of study.

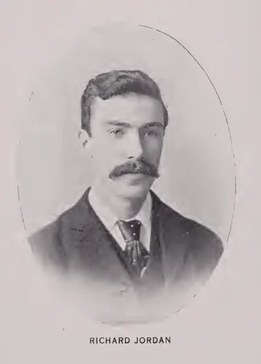

Public Domain

There is practically no limit to the amount that one can learn. Richard Jordan, for example, early in his meteoric career, defeated three famous world champions--- James Ferrie, Robert Stewart, and James Wyllie; and he himself became world champion in 1896. Moreover, in 1897, he again defeated Robert Stewart. Richard Jordan could play 20 games simultaneously at an exhibition while blindfolded; then he could repeat all of them from memory; and in addition he could remember those games backward. He apparently enjoyed recalling games that he had played.

Repeat and repeat from memory--- not from the book; then your memory troubles will not be so bad.

Public Domain

Certainly modern theory supports the idea of learning by repetition at spaced intervals, as famously championed by the SuperMemo system and many others; but Mr. Banks unfortunately doesn't address the main question. Should memorization be a part of checker study? Some say yes, some say no. Dr. Tinsley expressed the view that checkers is more about what you see than what you remember. Others say that memorization is a necessary part of preparation, especially with some 3-move ballots. What do you think?

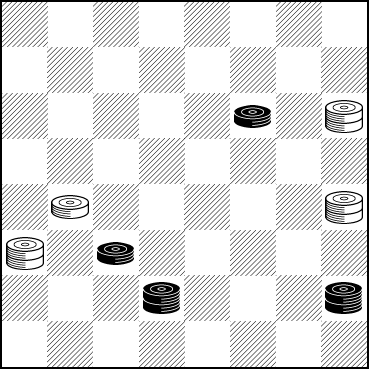

Here's a problem from the selfsame book. Would any amount of prior memorization help you solve it? Perhaps that's an irrelevant question to ask about a "gem" problem, as Mr. Banks styles this one--- or is it?

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:WK12,17,K20,K21:B11,22,K26,K28

You decide. Solve the problem and then click on Read More to see the solution. And do write to us with your thoughts on memorization in checkers.![]()

Solution

Notes are by Mr. Banks.

12-8---A 11-15 *20-24---B 28-19 8-11---A 15-18 11-15---C 19-10 17-14 10-17 21-30---D White Wins.

A---Threat to steal.

B---Sacrifice to press man.

C---Illustrates the back jump.

D---"Western Weekly Mercury" Feb. 1919.

We can't say that any particular memorization would have helped here; solving this one is a matter of vision. Of course having solved similar problems in the past would definitely help, but is that more a matter of pattern recognition than memorization of the type our friend Hatley was attempting?

Interesting questions indeed, perhaps worthy of academic study one day, maybe even as the subject of a doctoral thesis!

You can email the Webmaster with comments on this article.