The Checker Maven

The Deckhand

The deckhand in the photo above appears to be contemplating some sort of difficult shipboard task, and she doesn't appear too anxious to get about her business. Can't say that we blame her; some pretty heavy work happens on a commercial sailing vessel.

We're sure, though, that you won't have similar reluctance in tackling today's checker problem, which was composed by Chris Nelson, who used the nom-de-plume of "The Deckhand." We don't know why Mr. Nelson, who was a denizen of Brooklyn, chose this pseudonym. Perhaps he was a spare-time sailor. But we can say for sure that he was a fine checker problem composer, as the offering below will handily demonstrate.

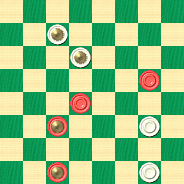

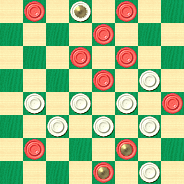

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:WK6,K10,24,32:B16,18,K22,K30.

Get on board and solve this problem. It may not be as hard as shipboard labor, but it presents a nice little challenge. Then sail your mouse over to Read More to see the solution.![]()

A Thinker's Game

Those of us who play checkers in any sort of serious manner know very well that checkers is indeed a "thinker's" game, despite our oft-repeated laments that the general public doesn't usually share that opinion. Today's entry in our ongoing Checker School series demonstrates the fine line that can separate victory from just another drawn game; it takes a real thinker to see the difference between moves that look very similar but are far from it.

The situation is diagrammed below.

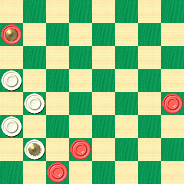

WHITE

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W20,16,12,K8:BK28,13,7,3.

You'll see in the solution notes and sample game the interesting manner in which this position came about, but for now, can you think your way to a Black victory, or will a thoughtless move give up your winning chances? Think it over, and then click on Read More to see the solution, thoughtful notes, and a sample game.![]()

The Jaywalker Gambit

If you visit Honolulu, you'd best not jaywalk; the fine is a whopping one hundred and thirty dollars, and the police don't hesitate to hand out the tickets. Jaywalking is a gambit you won't want to risk; it could really cost you.

There's a Jaywalker Gambit in checkers, too, and it won't cost you a cent to hear how Willie Ryan describes it in his classic book, Tricks Traps & Shots of the Checkerboard.

"The late great A. J. Heffner, of Boston, former Champion of America and heralded as one of the greatest analysts of all time, was responsible for christening the following trap 'the Jaywalker,' pointing out that many experts had wandered into it, unaware of their predicament until it was too late to bail out. The Jaywalker, a formational 'natural,' was originally rated drawable on the basis of Tillum and Aitchison's play, as quoted in the trunk game. But the eminent British authority, J. A. Kear, of Bristol, England, published an analysis indicating that, by introducing the 16-19 move at Note E, the gambit ended in defeat. Kear's play remained unchallenged for many years, but the data assembled here indicate that Kear's 16-19 move is nothing more than a transposition that ultimately runs back into the Tillum and Aitchison draw. Play:

| 11-16 | 30-26 | 7-10 |

| 24-19 | 11-16 | 26-22---2 |

| 8-11 | 22-17---A | 10-14, |

| 22-18 | 4-8 | forming the |

| 10-14 | 17-10 | diagram. |

| 26-22 | 6-24 | |

| 16-20 | 28-19 | |

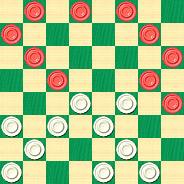

WHITE

White to Play and Draw

W:W32,31,29,27,25,23,22,21,19,18:B20,16,14,12,9,8,5,3,2,1.

A---A very weak move---1, forming the famous Jaywalker position. The correct play here for a draw is: 28-24, 4-8, 22-17, 7-10, 26-22, 3-7---B, 19-15, 10-26, 17-3, 26-30, 18-15, 6-10, 15-6, 1-10, 31-26, 30-23, 27-18, 20-27, 32-23, 9-13, 21-17, 5-9, 25-21, 2-7, 29-25, 7-11, 3-7, 10-14, 17-10, 16-20, 7-16, 12-26. Wm. F. Ryan.

B---White has a pretty trap here, for if the play goes 9-13, 18-9, 5-14, white wins by storm with: 19-15!, 10-26, 17-10, 6-15, 22-17, 13-22, 25-4, 26-30, 4-8. D. G. McKelvie."

1---The computer sees 22-17 as only very slightly worse than 28-24, so we're not sure why Willie thinks it's so weak. Perhaps the position is simply more difficult to play correctly---Ed.

2---Here's the real problem. The text move is substantially weaker than 25-22, though still not losing. Perhaps Willie should have flagged this move instead---Ed.

Don't be a jaywalker; walk the straight and narrow and solve the position. But we won't fine you if you don't get it; you can always safely click on Read More to see the solution and detailed notes.![]()

One Stroke

The item shown above is called a "one-stroke" brush, intended for use with the "FolkArt One Stroke" painting technique. Though we know very little about this brush technique, it certainly sounds fascinating.

We've never claimed to know a lot about our game of checkers, either, but today we present "one" stroke problem, and solving it it will call into play the technique of checker visualization, which we believe to be a fascinating art form in its own right.

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W32,24,23,22,19,18,17,16,K2:BK31,K27,25,20,15,11,10,7,3,1.

Now that's "one" stroke problem! Try to solve it without moving the pieces; when you've had your brush with this one, sweep your mouse to Read More to see the solution.![]()