The Checker Maven

Problem Composition Contests Are Back!

Old-fashioned checker problem composition contests are back, thanks to the efforts of master problemist William J. (Bill) Salot.

If you're at all familiar with checker literature, you know that solving checker problems provides an essential means of improving your game. Time and again, the experts advise us make the solution of checker problems a regular part of our study routine.

But checker problems go far beyond mere didactic purposes. A fine problem provides exquisite pleasure to the solver, and gives a view into the depth and beauty of the game of checkers.

Composing a truly great problem, a "gem" if you will, combines both art and science, with much emphasis on art. Mr. Salot is such a modern-day artist, and his goal is to start a neo-renaissance in the enjoyment and composition of checker problems.

To this end, he's started a series of problem composition contests; they've been running monthly since January 2012, with the third such contest now in progress. The prize is the designation of "unofficial world champion" problem compositor. More details and problems and solutions for both the current and previous competitions can be found here. Be sure to check this out and cast your vote for the problem you think is best.

Don't miss out. The contest problems are elegant and entertaining. Some of them are truly astounding.

Mr. Salot was very kind in granting The Checker Maven an email interview. Mr. Salot also gave us a problem composed earlier in his career, which you'll find at the end of today's column. But first, let's talk with Mr. Salot for a little while.

What gave you the idea for the problem composition contests?

I had been composing, collecting, and publishing occasional checker problems for many years. Then I fell away from the game for a few decades. When I returned to the game a few years ago, I still had the problem composing bug. But there were far fewer places to publish problems, and apparently fewer problemists too. The current contests are just a natural revival of those conducted for several years beginning in the October 1969 ACF Bulletin. Whether they will uncover many “budding” problemists remains to be seen.

How would you characterize the response so far, both from the standpoint of problemists making submissions, and audience participation?

Using the Internet has proved to be a huge advantage over the old days when everything moved by “snail” mail. The audience response in terms of the number of judges has increased from 7 in a trial contest, to 12 in Contest #1, to 35 in Contest #2. We never had more than 6 judges before the Internet. The number of competing problemists is also growing, but not that fast. We would like to have more.

How did you get interested in composing problems?

As a beginner, I did not have frequent opportunities to play across the board. My few books each had a problem section in front of the games section. I reviewed the problems first. After that, the games in contrast seemed incomplete and largely incomprehensible. As a matter of curiosity, I found myself exploring options not covered in the games. Sometimes I could make the options more interesting by doctoring the positions. That was how I got into composing.

Can you tell us about your career as a problemist?

That so-called career would have disappeared early had I not subscribed to Willie Ryan’s highly entertaining American Checkerist magazine. I sent Ryan my first problem, he said it was a hit at the NYC Club and published it, probably because a “kid” composed it. That hooked me. My “career as a problemist” has been mostly sporadic. I spent some years helping Ernie Churchill produce “Churchill’s Compilations”; and some other years collecting problems, primarily those by George H. Slocum; but mostly I have been earning a living as a professional engineer (58 years and still counting) and raising a family (3 middle-aged kids and a grandson).

What advice might you have for the budding checker problemist?

Enjoy whatever facets of the game please you most, whether it be playing or chatting with friends nearby or on the Internet; participating in crossboard tournaments for prizes or fun; collecting or researching the literature; or analyzing positions with the aim of creating either a good cook or a good problem. If you want to open the door to problem composing, forget competition, relax and treat the challenge as a true artist. Learn to appreciate the artwork of others; then take all of the time necessary to create your own. Be both your own worst critic and your own best motivator. Never give up. The product may takes weeks, even months, but the process is uplifting, not drudgery. Check every crazy move, including backwards. Utilize a computer program; it can’t compose, but it can facilitate. Each composition is a learning experience toward making the next one better. Don’t listen if someone advises you, as I was advised, to take up tennis.

What do you think makes for a good checker problem?

That is what I have been trying to find out for more than 65 years. The answer is in the eyes of the beholder. Evaluation of contest problems is seldom unanimous. You favor one style. I favor another. Composers should always favor sound, dual-free problems that feel right, without regard to the style of problem. Abhor optional sequences; try to make every move a star.

Do problems have to be difficult to be good?

No, a single move can be good. Problems with very few moves have been called gems. The most difficult problem may not win a contest. Difficulty and beauty are not synonymous.

What do you think about problems aimed at beginning and intermediate players?

Many are needed and should be assimilated by beginners and intermediate players before advancing too far. Such problems would not fare well in a contest unless the contest did not include any advanced ones.

Is there a distinction here between "teaching" problems and "artistic" problems?

They probably overlap. “Teaching” to me implies a practical objective for use in a game; e.g., standard positions. “Artistic” problems that have arisen in games have a practical “teaching” attribute. But many “artistic” problems are unlikely or cannot possibly arise in a game; they probably “teach” nothing more than appreciation of the art. The distinction is not always obvious. Some very natural-appearing settings cannot arise in a game, while some extremely unnatural settings have.

Stroke problems sometimes evoke strong likes or dislikes. What's your opinion on stroke problems?

I have composed a couple of pure strokes of which I am very proud. Probably most composers have. Big pure strokes are very difficult to create without dual solutions or optional sequences. Accomplishing such perfection deserves more recognition than it usually gets. On the other hand, deferred strokes (Slocum strokes) are seldom disliked.

What do you see for the future of your problem contests?

Past problem composing contests have seldom lasted more then a few years unless they are widely spaced. The primary cause is composer exhaustion. The way the current contests are set up, the contest frequency can be varied to accommodate the arrival frequency of new problems. I can see the current contests becoming only annual events and still surviving.

Do you think checker problem composition has a bright future in general?

I think its future is linked to the future of the game itself. Together they have a synergy that should thrive for a good while. At my age, I don’t look too far into the future.

Anything else you'd like to say to Checker Maven readers?

I would like to see some of these things discussed more widely. But more importantly, I would like to pull more talented checkerists into the problemists’ arena. I believe they would thrive.

Thank you, Mr. Salot, for taking the time to talk with us. And now, as promised, here's one of Bill's problems.

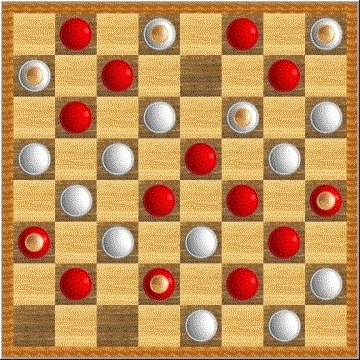

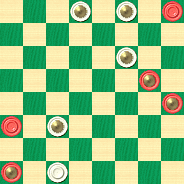

BLACK

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:B3,11,28,K29:WK10,12,K18,27.

Give it a try; it's just fine if you take your time and are a slo-poke yourself. When you're done, slo-ly poke your mouse on Read More to see the solution and Mr. Salot's problem notes.![]()

Conroy's Slider

Public Domain Pictures CC0

Our Research Department told us, when asked to find a theme for today's entry in our ongoing Checker School series, that there is a bar on Conroy Road in Orlando, Florida, that serves sliders, those small hamburgers that simply slide on down. In fact, they continued, there is a catering establishment in the selfsame Conroy area that features sliders ... we asked them to stop there, that's quite enough, thank you.

We're certain that old-time checker editor J. A. Conroy, after whom the position shown below is named, never had a slider in his life, whether at a bar or catered or in any other form. He lived about 150 years too early for that, and we can speculate that he was likely the better for it. Why the position is called a "slider" will be clear when you work out the solution, and we suppose you've already guessed that hamburgers have nothing to do with it.

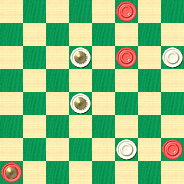

BLACK

Black to Play and Draw

B:W25,22,19,18:B13,11,10,5.

Can you slip through this one, or will you get stuck on the way? Try it out--- it goes down easy--- and then slide your mouse over to Read More to see the solution, notes, and sample games.![]()

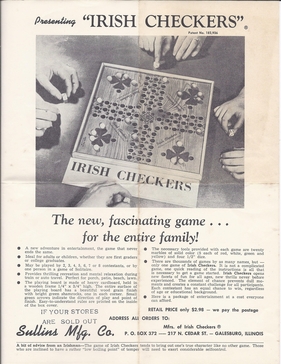

Irish Checkers

Public Domain

This column will appear on St. Patrick's Day, the traditional Irish holiday filled with festivities such as parades, music, green beer, corned beef and cabbage, and much song and merriment. We wish all the celebrants the top o'the day.

We don't know if Irish Checkers will be part of any of the local celebrations, and in fact we have our doubts. Irish Checkers is a proprietary game reportedly created in 1957 by Sullins Manufacturing Company, a one-man operation in Galesburg, Illinois. The game, which is neither Irish nor checkers (and if it had been Irish, it would have been called "draughts'), looked to have been a combination of Halma and Chinese Checkers (which itself is neither Chinese nor checkers) with some dice added to create a strong element of chance. Intriguing, perhaps, but the game didn't last very long, perhaps only a year or so, and Sullins Manufacturing lasted little longer.

Now, we wanted to publish a problem from an historical edition of the Irish Times but we quickly found that access to the Times archives comes with a steep enough price tag to earn an instant turn-down from our corporate accountant. So instead we'll publish a problem that, while not in itself Irish, might require "the luck o'the Irish" to solve.

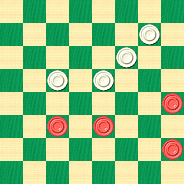

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:WK2,K3,K11,K22,30:B4,K16,K20,21,K29.

Will this problem make you turn green? Will you be reduced to boiled cabbage? Or will you employ a bit of Irish wit and wisdom, and find the solution? When you've given it a good Irish try, click your mouse on Read More to see the solution.![]()

A Denny Dandy

What could be as dandy as breakfast at Denny's, that great American "breakfast at any hour" institution? We're sure nearly all of us who live in the U.S. can confess to indulging in such an extravagant "count no calories" morning feast at least once in recent memory.

But there is something just as dandy as Denny's, and that's today's Denny Dandy in our latest excerpt from Willie Ryan's Tricks Traps & Shots of the Checkerboard. We're sure you'll enjoy it, and it's guaranteed to be calorie free. Here's Willie to tell us all about it.

"Very often it is necessary to force a win by the constant threat of a shot without ever actually executing it. In other cases, execution of a shot may be the final product of much preliminary forced play. Here we have a good example of white developing a structural advantage (formational win) in such a manner as ultimately to force black into a staggering stroke. It should be noted that in this case the stroke is the final phase of play, with white's preceding moves forcing black into the inevitable crackup.

| 10-14 | 20-16 | 1-5 |

| 24-20 | 12-19 | 24-20 |

| 7-10 | 23-16 | 5-9 |

| 22-18 | 14-18---A | 32-27 |

| 9-13 | 29-25 | 9-14 |

| 18-9 | 8-12 | 27-24 |

| 5-14 | 16-11 | 3-8---3, |

| 25-22 | 12-16---2 | to the |

| 11-15 | 27-24 | diagram. |

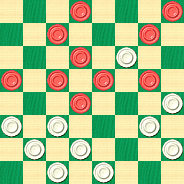

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W31,30,28,26,25,24,22,21,20,11:B18,16,15,14,13,10,8,6,4,2.

A---I took this move against Jesse B. Hanson in the Eighth American Championship Tourney and managed to draw with it. Later, in analyzing the formation, I discovered it would lose, white subsequently driving black into the shot, as indicated. The correct play at A for a draw is: 2-7---1, 16-12, 15-19, 22-18, 14-23, 27-18, 8-11, 18-14, 10-17, 21-14, 1-5, 32-27, 6-9, etc. Wm. F. Ryan."

1---8-12 is also good for a draw and is the computer's choice---Ed.

2---A bit surprisingly, the natural-looking 3-7 loses something like this: 3-7 26-23 7-16 23-7 2-11 21-17 6-9 27-23 4-8

31-27 15-19 23-18 19-23 17-14 1-5 14-10 16-19 18-15 11x18 22x15 White Wins---Ed.

3---Loses at once, whereas 16-19 would have held on longer---Ed.

We'd like to egg you on: ham it up a little and bring home the bacon on today's problem. Or will you be toast? We won't try to butter you up; simply clicking on Read More will get you out of a jam and over to the solution.![]()

In Like a Lamb

It is traditionally said that March may "come in like a lamb and go out like a lion" or conversely "come in like a lion and go out like a lamb."

Our columns are written quite a few weeks in advance of their publication date, so we won't attempt to predict March weather in North America; that's an iffy proposition in any event.

But one thing we can do is bring March in "like a lamb" with a relatively easy top of the month stroke problem.

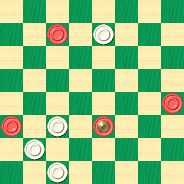

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W7,22,25,30:B6,20,21,K23.

So, are you a lion or a lamb? Will you roar past this problem or be meek as a lamb? We can't predict that, either, but we can say for sure that clicking your mouse on Read More will reveal the problem's solution. And here's hoping that March weather won't be too difficult, either.![]()