Don't be a Square

"Don't be a square" is probably an expression you haven't heard much lately, as it's long out of date. It actually originated with jazz musicians but by the 1980s, it was starting to sound old-fashioned.

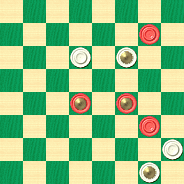

Our use of this phrase to title our column is for two reasons. The first is the shape seen in the problem diagram.

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W23,K22,5,K1:B25,K15,K14,9.

The second meaning derives from the solution itself. You might see what we're getting at when you solve it. It's not overly difficult. Don't be a square--- try to work it out. When you're finished, click your mouse squarely on Read More to see the solution and an explanation.![]()

Solution

Here's the "square" solution.

25-30---A 22-26---B 14-10 26-22 9-14 22-26 30-25 26-31 25-22 31-27 22-26 Black Wins.

A---29-25 1-6 to a draw.

B---See alternate solution below for play on 1-6.

Very workmanlike and steady, if lacking a bit in fireworks. We expect that the following, however, was the problem composer's proposed solution.

25-30 1-6 14-17 22x13 15-10 6x15 30-26 13x6 26x1 Black Wins.

Much more pleasing and exciting! The composer likely didn't want to be a square and desired to present something with a lot of action. But White didn't have to play 1-6 and grant Black's wishes, hence the first solution, which actually features better if less spectacular play. The moral of the story? Sometimes it's okay to be a square!

Addendum: Soon after publication of this column, we received a note purportedly from George H. Slocum, sent by means of his medium, William Salot, which we think correctly challenges our assertion that 22-26 is better play than 1-6.

Mr. Newell:

Your exact setting of "Donít be a Square" was first published by Yours Truly on November 1, 1893 in the American Checker Review, Vol. V, Page 174, Prob. 98. (You will find it in Bolandís Familiar Themes, Page 34, No. 2, Salot).

I disagree with your claim, in Note B, that after 25-30, the 22-26 response "actually features better" play. Instead that response loses easily in several ways; namely, by 15-18 or 14-18 or 14-10. If advocating that play makes what you call a "square," I donít care to apply.

I would be remiss not to mention that Will H. Tyson, Big Run, Pennsylvania, pointed out, in the June and July 1911, dual issue of Canadian Checker Player, Volume 5, Page 146, that "we must credit it to William Barrenger of Pierson, Mich., who wins the setting with single piece on 14 instead of its being a king as others have it." In my opinion, the Barrenger setting is what "actually features better play." It eliminates the optional wins at your Note B. It appeared in the New England Checker Player, June 1881 (Vol. VI, No. 66), Problem 598. (You will find it in Bolandís Familiar Themes, Page 34, No. 1, Salot).

Regarding what you call "The Crocodile Position," you will find earlier, but not better, versions by Yours Truly in the April 1, 1892, American Checker Review, Vol. IV, Page 63, Prob. 38, and in the November 1, 1893, American Checker Review, Vol. V, Page 174, Prob. 97. (They are #44 and #55 in the SLOCUM STROKES book, Boland ignored them, Salot).

Yours truly,

George H. Slocum

We can only say in our defense that 1-6 and 22-26 are the only moves that do not pitch a piece (which is what the computer prefers to do here).

You can email the Webmaster with comments on this article.